Difference between revisions of "Training Monotony"

User:Fellrnr (User talk:Fellrnr | contribs) |

User:Fellrnr (User talk:Fellrnr | contribs) |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[File:Tired athlete.jpg|right|thumb|350px|Monotonous training produces increased fatigue and is a risk factor for | + | [[File:Tired athlete.jpg|right|thumb|350px|Monotonous training produces increased fatigue and is a risk factor for [[Overtraining]] and [[Overtraining Syndrome]].]] |

| − | It is long been recognized the athletes cannot train hard every day. Modern training plans recommend a few hard days per week, with the other days as easier or rest days. A lack of variety in training stress, known as | + | Training Monotony is not about boredom, but is a way of measuring the similarity of daily training. By calculating a simple number, it's easy to evaluate a training program, and understand its effectiveness. Training Monotony can be calculated using a spreadsheet or using Runalyze.com or TrainAsOne.com. The calculation is based on [[TRIMP| each day's training stress]], dividing the average by the standard deviation for each rolling seven day period. |

| − | + | =Training Monotony and Overtraining= | |

| + | It is long been recognized the athletes cannot train hard every day. Modern training plans recommend a few hard days per week, with the other days as easier or rest days. A lack of variety in training stress, known as Training Monotony, is considered a key factor in causing [[Overtraining Syndrome]]<ref name="Meeusen-2013"/><ref name="Armstrong-2002"/>. There is also evidence<ref name="Busso-2003"/> that increased training frequency results in reduced performance benefits from identical training sessions as well as increased fatigue. | ||

| + | =Training Monotony and Supercompensation= | ||

| + | Training Monotony is related to [[Supercompensation]] and the need for adequate rest to recover from training. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |- valign="top" | ||

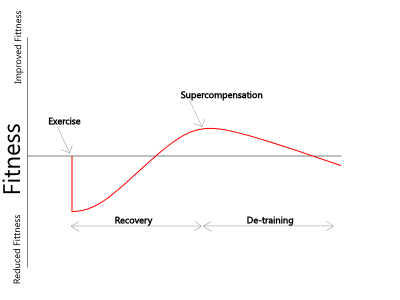

| + | |[[File:Supercompensation-small.png|none|thumb|x300px|Exercise produces a temporary decrease in fitness, followed by a recovery and [[Supercompensation]].]] | ||

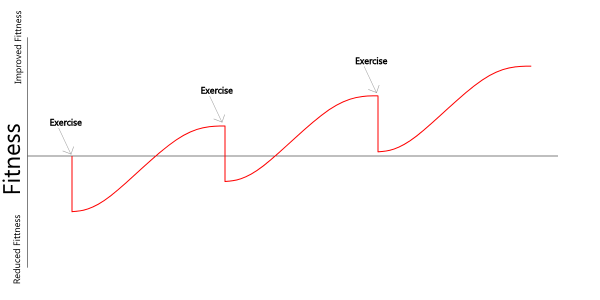

| + | |[[File:Supercompensation-continued-small.png|none|thumb|x300px|With sufficient rest between workouts, fitness improves.]] | ||

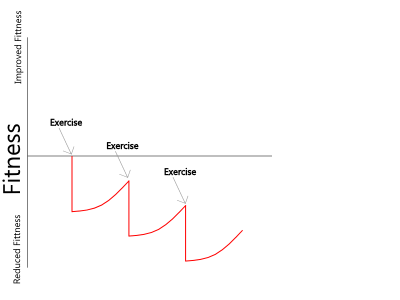

| + | |[[File:Supercompensation-fatigue-small.png|none|thumb|x300px|Without sufficient recovery time, the fatigue builds up until injury or [[Overtraining Syndrome]] occurs.]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

=Quantifying monotony= | =Quantifying monotony= | ||

| − | One approach<ref name=" | + | One approach<ref name="Foster-1998"/> to measuring monotony is statistically analyze the variation in workouts. The first stage is to work out a measure of the daily [[TRIMP]] ([[Training Impulse|TRaining IMPulse]]). From this daily [[TRIMP]] it's possible to calculate the standard deviation for each 7 day period. The relationship between the daily average [[TRIMP]] value and the standard deviation can provide a metric for monotony. The monotony value combined with the overall training level can be used to evaluate the likelihood of [[Overtraining Syndrome]]. |

| − | |||

=Monotony Calculations= | =Monotony Calculations= | ||

| − | The original work<ref name=" | + | The original work<ref name="Foster-1998"/> on training monotony used [[TRIMP]]<sup>cr10</sup> and [[TRIMP]]<sup>zone</sup>, but I substitute [[TRIMP]]<sup>exp</sup> for [[TRIMP]]<sup>zone</sup> because of the advantages noted in [[TRIMP]]. (Simply using daily mileage or duration could be used to get an estimate of Training Monotony.) From the daily [[TRIMP]] values for a given 7 day period the standard deviation can be calculated. (If there is more than one workout in a day, the [[TRIMP]] values for each are simply added together.) The monotony can be calculated using |

Monotony = average([[TRIMP]])/stddev([[TRIMP]]) | Monotony = average([[TRIMP]])/stddev([[TRIMP]]) | ||

This gives a value of monotony that tends towards infinity as stddev([[TRIMP]]) tends towards zero, so I cap Monotony to a maximum value of 10. Without this cap, the value tends to be unreasonably sensitive to high levels of monotony. Values of Monotony over 2.0 are generally considered too high, and values below 1.5 are preferable. A high value for Monotony indicates that the training program is ineffective. This could be because the athlete is doing a low level of training; an extreme example would be a well-trained runner doing a single easy mile every day. This would allow for complete recovery, but would not provide the stimulus for improvement and would likely lead to rapid detraining. At the other extreme, doing a hard work out every day would be monotonous and not allow sufficient time to recover. The Training Strain below can help determine the difference between monotonous training that is inadequate and monotonous training that is excessive. | This gives a value of monotony that tends towards infinity as stddev([[TRIMP]]) tends towards zero, so I cap Monotony to a maximum value of 10. Without this cap, the value tends to be unreasonably sensitive to high levels of monotony. Values of Monotony over 2.0 are generally considered too high, and values below 1.5 are preferable. A high value for Monotony indicates that the training program is ineffective. This could be because the athlete is doing a low level of training; an extreme example would be a well-trained runner doing a single easy mile every day. This would allow for complete recovery, but would not provide the stimulus for improvement and would likely lead to rapid detraining. At the other extreme, doing a hard work out every day would be monotonous and not allow sufficient time to recover. The Training Strain below can help determine the difference between monotonous training that is inadequate and monotonous training that is excessive. | ||

| − | + | ==Updated Monotony Formula== | |

| + | The formula above Is useful, but Its sensitivity to higher levels of monotony can overwhelm Your training data. This is particularly obvious when using the training strain calculations below. A small modification results in Training monotony values between 0.29 and 1.0. Here is the updated formula: | ||

| + | Monotony = average([[TRIMP]])/( stddev([[TRIMP]]) + average([[TRIMP]]) ) | ||

| + | When the standard deviation tends toward zero, the monotony value now tends towards 1.0 rather than Infinity. The highest standard deviation in a seven day period is from a single training day, combined with six days of rest. This results in a monotony of about 0.2899. (Note that you can still get a divide by zero error if there is no training load for the entire week, as both average and standard deviation are both zero. Treating this as a special case and assuming a training monotony of either 0 or 0.2899 is probably reasonable depending on usage.) | ||

=Training Strain Calculations= | =Training Strain Calculations= | ||

A similar calculation can be used to calculate a value for Training Strain. | A similar calculation can be used to calculate a value for Training Strain. | ||

Training Strain = sum([[TRIMP]]) * Monotony | Training Strain = sum([[TRIMP]]) * Monotony | ||

| − | The value of Training Strain that leads to actual | + | The value of Training Strain that leads to actual [[Overtraining Syndrome]] would be specific to each athlete. An elite level athlete will be able to train up much higher levels than a beginner. However this Training Strain provides a better metric of the overall stress that an athlete is undergoing than simply looking at training volume. |

| − | |||

=A simple [[TRIMP]]<sup>cr10</sup> based calculator= | =A simple [[TRIMP]]<sup>cr10</sup> based calculator= | ||

This calculator will show the [[TRIMP]]<sup>cr10</sup> values for each day, the Monotony, the total [[TRIMP]]<sup>cr10</sup> for the week and the Training Strain. | This calculator will show the [[TRIMP]]<sup>cr10</sup> values for each day, the Monotony, the total [[TRIMP]]<sup>cr10</sup> for the week and the Training Strain. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 50: | ||

i = numArr.length, | i = numArr.length, | ||

v = 0; | v = 0; | ||

| − | |||

while( i-- ){ | while( i-- ){ | ||

v += Math.pow( (numArr[ i ] - avg), 2 ); | v += Math.pow( (numArr[ i ] - avg), 2 ); | ||

| Line 52: | Line 61: | ||

return getNumWithSetDec( stdDev, numOfDec ); | return getNumWithSetDec( stdDev, numOfDec ); | ||

}; | }; | ||

| − | |||

function doTrimp(dur, cr10, trimp) | function doTrimp(dur, cr10, trimp) | ||

{ | { | ||

| Line 83: | Line 91: | ||

} | } | ||

</script> | </script> | ||

| − | |||

<form style="font-family: Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif;border: solid 2px #40a0c0" id="MonotonyForm"> | <form style="font-family: Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif;border: solid 2px #40a0c0" id="MonotonyForm"> | ||

<table style="text-align: left;" border="1" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="1"> | <table style="text-align: left;" border="1" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="1"> | ||

| Line 141: | Line 148: | ||

</form> | </form> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| − | |||

=TRIMP<sup>exp</sup> Examples= | =TRIMP<sup>exp</sup> Examples= | ||

| − | For these examples we will use just a few simple workouts. Let's assume a male athlete with a [[Maximum Heart Rate]] of 180 and a [[Resting Heart Rate]] of 40, giving a [[Heart Rate Reserve]] of 140. Let's assume our hypothetical athlete does his easy runs at a 9 min/mile pace and heart rate of 130. We'll use only one of the type of workout, a tempo run his easy runs at a 7 min/mile pace and heart rate of 160. This gives us some TRIMP<sup>exp</sup> values for some workouts | + | For these examples we will use just a few simple workouts. Let's assume a male athlete with a [[Maximum Heart Rate]] of 180 and a [[Resting Heart Rate]] of 40, giving a [[Heart Rate Reserve]] of 140. Let's assume our hypothetical athlete does his easy runs at a 9 min/mile pace and heart rate of 130. We'll use only one of the type of workout, a tempo run his easy runs at a 7 min/mile pace and heart rate of 160. This gives us some TRIMP<sup>exp</sup> values for some workouts. |

| − | {| class="wikitable" | + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; border: none;" |

| − | ! | + | ! |

| + | ! Miles | ||

| + | ! Duration | ||

| + | ! TRIMP<sup>exp</sup> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Easy | | + | | Easy |

| + | | 4 | ||

| + | | 36 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Easy | | + | | Easy |

| + | | 6 | ||

| + | | 54 | ||

| + | | 76 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Easy | | + | | Easy |

| + | | 10 | ||

| + | | 90 | ||

| + | | 127 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Easy | | + | | Easy |

| + | | 20 | ||

| + | | 180 | ||

| + | | 254 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Tempo | + | | Tempo |

| − | | | + | | 4 |

| − | + | | 28 | |

| + | | 80 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | Tempo | ||

| + | | 8 | ||

| + | | 56 | ||

| + | | 159 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | Here is a sample week's workout with three harder workouts, a 4 mile tempo, a 10 mile mid-long run and a 20 mile long run with four mile easy runs on the other days, a total of 50 miles. | |

| − | Here is a sample week's workout with three harder workouts, a 4 mile tempo, a 10 mile mid-long run and a 20 mile long run with four mile easy runs on the other days | + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; border: none;" |

| − | {| class="wikitable" | + | ! Monday |

| − | + | ! Tempo 4 | |

| − | + | ! 80 | |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Tuesday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Wednesday |

| + | | Easy 10 | ||

| + | | 127 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Thursday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Friday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Saturday |

| + | | Easy 20 | ||

| + | | 254 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Sunday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'>Stdev</span> |

| + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'> </span> | ||

| + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'>70</span> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style='color:#00B050'>Avg</span> |

| + | | <span style='color:#00B050'> </span> | ||

| + | | <span style='color:#00B050'>95</span> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Total |

| + | | | ||

| + | | 665 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Monotony |

| + | | | ||

| + | | 1.36 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | Training Strain | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | 903 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | If we give our athlete a single day's rest on Sunday, we reduce the mileage by 4 miles to 46 miles, total TRIMP<sup>exp</sup> goes down by 51, but the Monotony of drops more significantly to 1.15 and the Training Strain drops by 199. So the mileage has dropped about 9%, but the Training Strain has dropped by 22%. | |

| − | If we give our athlete a single day's rest on Sunday, we reduce the mileage by 4 miles to 46 miles, total TRIMP<sup>exp</sup> goes down | + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; border: none;" |

| − | {| class="wikitable" | + | ! Monday |

| − | + | ! Tempo 4 | |

| − | + | ! 80 | |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Tuesday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Wednesday |

| + | | Easy 10 | ||

| + | | 127 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Thursday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Friday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Saturday |

| + | | Easy 20 | ||

| + | | 254 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Sunday |

| + | | Rest | ||

| + | | 0 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'>Stdev</span> |

| + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'> </span> | ||

| + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'>77</span> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style='color:#00B050'>Avg</span> |

| + | | <span style='color:#00B050'> </span> | ||

| + | | <span style='color:#00B050'>88</span> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Total |

| + | | | ||

| + | | 614 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Monotony |

| + | | | ||

| + | | 1.15 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | Training Strain | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | 704 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | A further rest day on Tuesday drops the Training Strain by a further 21%. | |

| − | A further rest day on Tuesday drops the Training Strain by a further | + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; border: none;" |

| − | {| class="wikitable" | + | ! Monday |

| − | + | ! Tempo 4 | |

| + | ! 80 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Tuesday | + | | Tuesday |

| + | | Rest | ||

| + | | 0 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Wednesday | + | | Wednesday |

| + | | Easy 10 | ||

| + | | 127 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Thursday | + | | Thursday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Friday | + | | Friday |

| + | | Easy 4 | ||

| + | | 51 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Saturday | + | | Saturday |

| + | | Easy 20 | ||

| + | | 254 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Sunday | + | | Sunday |

| + | | Rest | ||

| + | | 0 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Stdev|| | + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'>Stdev</span> |

| + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'> </span> | ||

| + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'>82</span> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Avg|| | + | | <span style='color:#00B050'>Avg</span> |

| + | | <span style='color:#00B050'> </span> | ||

| + | | <span style='color:#00B050'>80</span> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Total|| | + | | Total |

| + | | | ||

| + | | 563 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Monotony| | + | | Monotony |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | 0.98 | |

|- | |- | ||

| + | | Training Strain | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | 553 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | If we compare this with an extreme example of a monotonous training plan, we have a slightly lower mileage (46 v 50), and a | + | If we compare this with an extreme example of a monotonous training plan, we have a slightly lower mileage (46 v 50), and a 57% lower total TRIMP<sup>exp</sup> (414 v 927), but the monotony is remarkably high at 4.7 and the training strain is 2.2x higher. In practice, there would be greater day to day variations, even within the same 6 mile easy run, so the results would not be quite so dramatic. |

| − | {| class="wikitable" | + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; border: none;" |

| − | + | ! Monday | |

| − | + | ! Easy 6 | |

| − | + | ! 54 | |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Tuesday |

| + | | Easy 6 | ||

| + | | 54 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Wednesday |

| + | | Easy 10 | ||

| + | | 90 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Thursday |

| + | | Easy 6 | ||

| + | | 54 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Friday |

| + | | Easy 6 | ||

| + | | 54 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Saturday |

| + | | Easy 6 | ||

| + | | 54 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Sunday |

| + | | Easy 6 | ||

| + | | 54 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'>Stdev</span> |

| + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'> </span> | ||

| + | | <span style='color:#FF0000'>13</span> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style='color:#00B050'>Avg</span> |

| + | | <span style='color:#00B050'> </span> | ||

| + | | <span style='color:#00B050'>59</span> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Total |

| + | | | ||

| + | | 414 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Monotony |

| + | | | ||

| + | | 4.69 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | Training Strain | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | 1,944 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

=References= | =References= | ||

<references> | <references> | ||

| − | <ref name=" | + | <ref name="Meeusen-2013">R. Meeusen, M. Duclos, C. Foster, A. Fry, M. Gleeson, D. Nieman, J. Raglin, G. Rietjens, J. Steinacker, Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 45, issue 1, pages 186-205, Jan 2013, doi [http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318279a10a 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318279a10a], PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23247672 23247672]</ref> |

| − | <ref name=" | + | <ref name="Foster-1998">C. Foster, Monitoring training in athletes with reference to overtraining syndrome., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 30, issue 7, pages 1164-8, Jul 1998, PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9662690 9662690]</ref> |

| − | <ref name=" | + | <ref name="Armstrong-2002">LE. Armstrong, JL. VanHeest, The unknown mechanism of the overtraining syndrome: clues from depression and psychoneuroimmunology., Sports Med, volume 32, issue 3, pages 185-209, 2002, PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11839081 11839081]</ref> |

| − | <ref name=" | + | <ref name="Busso-2003">T. Busso, Variable dose-response relationship between exercise training and performance., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 35, issue 7, pages 1188-95, Jul 2003, doi [http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000074465.13621.37 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074465.13621.37], PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12840641 12840641]</ref> |

</references> | </references> | ||

| + | [[Category:Advanced]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Science]] | ||

Latest revision as of 09:50, 17 April 2024

Training Monotony is not about boredom, but is a way of measuring the similarity of daily training. By calculating a simple number, it's easy to evaluate a training program, and understand its effectiveness. Training Monotony can be calculated using a spreadsheet or using Runalyze.com or TrainAsOne.com. The calculation is based on each day's training stress, dividing the average by the standard deviation for each rolling seven day period.

Contents

1 Training Monotony and Overtraining

It is long been recognized the athletes cannot train hard every day. Modern training plans recommend a few hard days per week, with the other days as easier or rest days. A lack of variety in training stress, known as Training Monotony, is considered a key factor in causing Overtraining Syndrome[1][2]. There is also evidence[3] that increased training frequency results in reduced performance benefits from identical training sessions as well as increased fatigue.

2 Training Monotony and Supercompensation

Training Monotony is related to Supercompensation and the need for adequate rest to recover from training.

Exercise produces a temporary decrease in fitness, followed by a recovery and Supercompensation. |

Without sufficient recovery time, the fatigue builds up until injury or Overtraining Syndrome occurs. |

3 Quantifying monotony

One approach[4] to measuring monotony is statistically analyze the variation in workouts. The first stage is to work out a measure of the daily TRIMP (TRaining IMPulse). From this daily TRIMP it's possible to calculate the standard deviation for each 7 day period. The relationship between the daily average TRIMP value and the standard deviation can provide a metric for monotony. The monotony value combined with the overall training level can be used to evaluate the likelihood of Overtraining Syndrome.

4 Monotony Calculations

The original work[4] on training monotony used TRIMPcr10 and TRIMPzone, but I substitute TRIMPexp for TRIMPzone because of the advantages noted in TRIMP. (Simply using daily mileage or duration could be used to get an estimate of Training Monotony.) From the daily TRIMP values for a given 7 day period the standard deviation can be calculated. (If there is more than one workout in a day, the TRIMP values for each are simply added together.) The monotony can be calculated using

Monotony = average(TRIMP)/stddev(TRIMP)

This gives a value of monotony that tends towards infinity as stddev(TRIMP) tends towards zero, so I cap Monotony to a maximum value of 10. Without this cap, the value tends to be unreasonably sensitive to high levels of monotony. Values of Monotony over 2.0 are generally considered too high, and values below 1.5 are preferable. A high value for Monotony indicates that the training program is ineffective. This could be because the athlete is doing a low level of training; an extreme example would be a well-trained runner doing a single easy mile every day. This would allow for complete recovery, but would not provide the stimulus for improvement and would likely lead to rapid detraining. At the other extreme, doing a hard work out every day would be monotonous and not allow sufficient time to recover. The Training Strain below can help determine the difference between monotonous training that is inadequate and monotonous training that is excessive.

4.1 Updated Monotony Formula

The formula above Is useful, but Its sensitivity to higher levels of monotony can overwhelm Your training data. This is particularly obvious when using the training strain calculations below. A small modification results in Training monotony values between 0.29 and 1.0. Here is the updated formula:

Monotony = average(TRIMP)/( stddev(TRIMP) + average(TRIMP) )

When the standard deviation tends toward zero, the monotony value now tends towards 1.0 rather than Infinity. The highest standard deviation in a seven day period is from a single training day, combined with six days of rest. This results in a monotony of about 0.2899. (Note that you can still get a divide by zero error if there is no training load for the entire week, as both average and standard deviation are both zero. Treating this as a special case and assuming a training monotony of either 0 or 0.2899 is probably reasonable depending on usage.)

5 Training Strain Calculations

A similar calculation can be used to calculate a value for Training Strain.

Training Strain = sum(TRIMP) * Monotony

The value of Training Strain that leads to actual Overtraining Syndrome would be specific to each athlete. An elite level athlete will be able to train up much higher levels than a beginner. However this Training Strain provides a better metric of the overall stress that an athlete is undergoing than simply looking at training volume.

6 A simple TRIMPcr10 based calculator

This calculator will show the TRIMPcr10 values for each day, the Monotony, the total TRIMPcr10 for the week and the Training Strain.

7 TRIMPexp Examples

For these examples we will use just a few simple workouts. Let's assume a male athlete with a Maximum Heart Rate of 180 and a Resting Heart Rate of 40, giving a Heart Rate Reserve of 140. Let's assume our hypothetical athlete does his easy runs at a 9 min/mile pace and heart rate of 130. We'll use only one of the type of workout, a tempo run his easy runs at a 7 min/mile pace and heart rate of 160. This gives us some TRIMPexp values for some workouts.

| Miles | Duration | TRIMPexp | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | 4 | 36 | 51 |

| Easy | 6 | 54 | 76 |

| Easy | 10 | 90 | 127 |

| Easy | 20 | 180 | 254 |

| Tempo | 4 | 28 | 80 |

| Tempo | 8 | 56 | 159 |

Here is a sample week's workout with three harder workouts, a 4 mile tempo, a 10 mile mid-long run and a 20 mile long run with four mile easy runs on the other days, a total of 50 miles.

| Monday | Tempo 4 | 80 |

|---|---|---|

| Tuesday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Wednesday | Easy 10 | 127 |

| Thursday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Friday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Saturday | Easy 20 | 254 |

| Sunday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Stdev | 70 | |

| Avg | 95 | |

| Total | 665 | |

| Monotony | 1.36 | |

| Training Strain | 903 |

If we give our athlete a single day's rest on Sunday, we reduce the mileage by 4 miles to 46 miles, total TRIMPexp goes down by 51, but the Monotony of drops more significantly to 1.15 and the Training Strain drops by 199. So the mileage has dropped about 9%, but the Training Strain has dropped by 22%.

| Monday | Tempo 4 | 80 |

|---|---|---|

| Tuesday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Wednesday | Easy 10 | 127 |

| Thursday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Friday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Saturday | Easy 20 | 254 |

| Sunday | Rest | 0 |

| Stdev | 77 | |

| Avg | 88 | |

| Total | 614 | |

| Monotony | 1.15 | |

| Training Strain | 704 |

A further rest day on Tuesday drops the Training Strain by a further 21%.

| Monday | Tempo 4 | 80 |

|---|---|---|

| Tuesday | Rest | 0 |

| Wednesday | Easy 10 | 127 |

| Thursday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Friday | Easy 4 | 51 |

| Saturday | Easy 20 | 254 |

| Sunday | Rest | 0 |

| Stdev | 82 | |

| Avg | 80 | |

| Total | 563 | |

| Monotony | 0.98 | |

| Training Strain | 553 |

If we compare this with an extreme example of a monotonous training plan, we have a slightly lower mileage (46 v 50), and a 57% lower total TRIMPexp (414 v 927), but the monotony is remarkably high at 4.7 and the training strain is 2.2x higher. In practice, there would be greater day to day variations, even within the same 6 mile easy run, so the results would not be quite so dramatic.

| Monday | Easy 6 | 54 |

|---|---|---|

| Tuesday | Easy 6 | 54 |

| Wednesday | Easy 10 | 90 |

| Thursday | Easy 6 | 54 |

| Friday | Easy 6 | 54 |

| Saturday | Easy 6 | 54 |

| Sunday | Easy 6 | 54 |

| Stdev | 13 | |

| Avg | 59 | |

| Total | 414 | |

| Monotony | 4.69 | |

| Training Strain | 1,944 |

8 References

- ↑ R. Meeusen, M. Duclos, C. Foster, A. Fry, M. Gleeson, D. Nieman, J. Raglin, G. Rietjens, J. Steinacker, Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 45, issue 1, pages 186-205, Jan 2013, doi 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318279a10a, PMID 23247672

- ↑ LE. Armstrong, JL. VanHeest, The unknown mechanism of the overtraining syndrome: clues from depression and psychoneuroimmunology., Sports Med, volume 32, issue 3, pages 185-209, 2002, PMID 11839081

- ↑ T. Busso, Variable dose-response relationship between exercise training and performance., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 35, issue 7, pages 1188-95, Jul 2003, doi 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074465.13621.37, PMID 12840641

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 C. Foster, Monitoring training in athletes with reference to overtraining syndrome., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 30, issue 7, pages 1164-8, Jul 1998, PMID 9662690