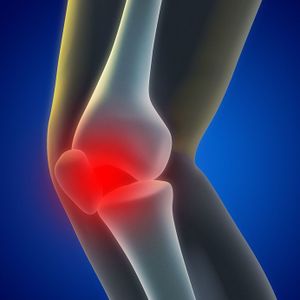

Knee Pain (Runner's Knee)

A pain behind the kneecap is one of the most common problems for runners[1], so much so that it is sometimes referred to as 'runners knee'[2]. There is no well-established cure for this problem[3], but there are a number of things you can try and some treatments to avoid. This article looks at the possible causes of knee pain, the treatment options, and things to avoid. While runners are often thought of as having more knee problems than non-runners, this is probably not the case[4]. This article focuses on pain behind the kneecap (Patellofemoral Pain), but you might have pain on outside of your knee or Medial Knee Pain.

Contents

1 Causes

There are a number of possible root causes of knee pain.

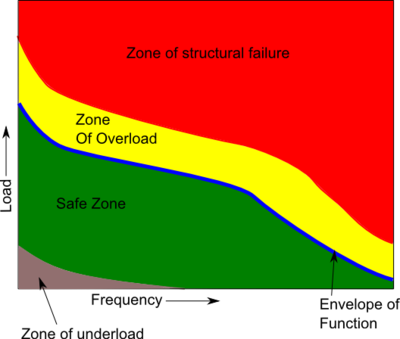

1.1 Excessive stress

The kneecap is an amazing structure, but like all body parts, it has limits in the load it can take. This overload may be due to a number of factors.

- Low Cadence. Having a low Cadence results in more vertical movement, and thus higher landing forces. This is a relatively easy fix and fixing your Cadence has many other benefits.

- Obesity. Obviously being overweight puts more stress on the knees and is linked to knee pain[5].

- Bad Running Form. Problems with Running Form can increase the landing forces and cause injury.

- Overstriding. Overstriding is landing with the foot ahead of the hip, can increase the landing forces and cause injury[6].

- Heel strike. Landing with the weight on the heel of the foot creates a greater peak force than landing so the weight is taken by the midfoot or forefoot[7]. See Foot Strike for more details.

- Highly cushioned shoes. Counterintuitively, the more cushioned your shoes are, the greater the loading force on your knees[8][9]. See The Science of Running Shoes for more details.

- Motion control shoes. There is evidence that motion control shoes cause more pain for all runners, regardless of their arch height[10]. See The Science of Running Shoes for more details.

1.2 Inactivity

The human body needs activity to remain healthy, and the knee is a prime example of this. Animal studies have shown than complete immobilization of the knee can result in a 50% reduction in the cartilage thickness within weeks[11]. Thankfully this damage appears to be reversible.

1.3 Weak Quads

It is common for people with knee pain to have weak quads[12]. However, I have found no research to suggest that weak quads are a cause of knee pain, rather than a result of knee pain. I believe that it is more reasonable to conclude that knee pain results in less exercise as the patient avoids activities that cause pain, and thus the quads become weaker through inactivity.

1.4 Maltracking/malalignment

The kneecap moves in a groove in the thigh bone (femur), and it is widely believed[13] that if the kneecap does not track in this grove it will rub on the sides and cause knee pain. While this belief is not well supported by the evidence[14], the following underlying problems may still cause knee pain through other mechanisms.

- Weak VMO. The alignment of the kneecap is not related to the overall strength of the quads, but rather an imbalance of the muscles that make up the quads. The quads consist of four muscles, and a relative weakness in a subdivision of one muscle, the Vastus Medialis Obliquus or VMO, has been linked to kneecap alignment[15] and knee pain[16].

- VMO Delay. There is some evidence that people suffering from knee pain (PFPS) have a delay in the activation of the VMO compared with the main quad muscles[17][18], which reduced the lateral force by 25%[19]. Detecting this timing difference is normally requires sophisticated clinical equipment, but there is some suggestion that the delay can be felt directly by placing fingers on the belly of the VMO and the VL[12].

- Weak Hips. A weakness in the hip muscles has been linked to knee pain[20]. Weak hip muscles result in the leg rotating so the foot points towards the midline of the body (internal rotation), so when the leg bends extra stress is placed on the knee.

- Q Angle. The thigh bone and lower leg are not in a straight line, but form an angle at the knee called the 'Q Angle'. A large Q Angle is often thought to cause or contribute to knee pain, but a high Q Angle was only seen in 6% of knee pain (PFPS) cases[1] and a high Q angle is not associated with biomechanical knee stress[21].

- Over Pronation. Pronation is the natural movement of the foot where the arch flattens to absorb landing forces. If the foot pronates too much, the foot will lean towards the midline of the body and the lower leg and knee will follow this motion, moving towards the midline. Like weak hips, the movement of the knee towards the midline creates extra stress on the knee.

1.5 Arthritis

Arthritis is an inflammation of the joints and can affect the knee. There are various types of arthritis, and diagnosis requires X-Ray, testing the fluid around the joint or inserting a viewing scope into the joint. Arthritis is outside of the scope of this article.

1.6 Baker's cyst

A baker's cyst causes pain behind the knee joint rather than under the knee cap.

1.7 ITBS

Another common source of knee pain is Iliotibial band syndrome which generally causes pain to the outside of the knee. However, this can sometimes be confused with kneecap pain.

1.8 Fracture

A fracture of the kneecap will obviously cause knee pain, but is normally the result of trauma. If you suspect you have a fractured kneecap, seek medical help.

1.9 NSAIDs

Cartilage destruction is a major cause of concern with NSAIDs[22], but I found no long term studies that link NSAID use with knee problems, so it's not clear if this is a widespread cause of knee pain. See NSAIDs and Running for more details.

1.10 Chondromalacia

The term Chondromalacia means soft cartilage and was once thought to be a common cause of knee pain. However, studies have shown that people with advanced Chondromalacia can be pain free[3].

1.11 Leg length discrepancy

A difference in leg length can be a factor in knee pain[12]. If you're concerned about having a possible leg length difference, it's best to get this evaluated by a specialist as misalignment of the hips can give the appearance of different leg lengths.

2 Treatments

This list is roughly in order of the viability and priority of the treatments.

- Cadence. If you're cadence is too low it can cause various problems, and should be optimized to around 180 steps per minute (90 steps/min for each leg). See Cadence for more details.

- Reduce Knee Stress. Stress on the knee should be reduced to prevent further damage[12]. Personally, I do not believe in complete rest, but prefer reduced exercise, trying to avoid or minimize pain as I believe the exercise promotes healing.

- Ice. The use of ice will not remove the underlying cause of knee pain, but it can help with recovery and healing. See Cryotherapy for more details.

- Massage the VMO. While the evidence for weak quads and VMO is marginal, massaging the VMO is easy and reasonably risk free. While the Foam Roller is good for massaging most of the quads, it tends not to get to the VMO, and if the Foam Roller is your only quad massage technique then it's possible that your VMO is suffering from neglect. I would recommend using The Stick as well as using your elbow on the VMO. I've also found that using an electronic muscle stimulator on the VMO can help. See main article on Massage for more details.

- Massage the glutes. Weak glute muscles have been linked to knee pain[20][23], so massaging them may help them recover their strength and functionality.

- Electrical Muscle Stimulation. Strengthening the quad muscles using normal resistance training tends to put extra stress on the kneecap aggravating the injury. Resistance training the quad muscles tends to equally train all parts, rather than focusing on the VMO. The only known way to selectively strengthen the VMO is by the use of Electrical Muscle Stimulation[12]. See Electrical Muscle Stimulation for more details.

- Footwear. There are two types of footwear changes that may help with knee pain that are contradictory; minimalist footwear and orthotics. Personally, I am concerned that Orthotics may help with knee pain but cause other problems, and the use of orthotics goes against the evidence for minimalist footwear. However, there is more scientific evidence to support orthotics for resolving knee pain, even though orthotics may increase knee stress. My personal belief is that it is better to cautiously move towards Minimalist Running Footwear rather than use orthotics, but I want to be clear that there is not clear scientific support for my belief.

- Minimalist shoes. There is good evidence that running shoes increase the stress on the knee[24], and that a more minimalist approach to footwear may be appropriate. There is plenty of anecdotal evidence[25] that minimalist footwear helps with knee pain, but only limited science[26] to back it up. Also, changing too quickly to minimalist footwear may result in Too Much Too Soon injuries. See 'The Science of Running Shoes' for more details.

- Orthotics. Studies have shown that orthotics reduce knee pain, with a greater benefit shown in those that have greater pronation[27][28][29]. However, there are concerns that orthotics may also increase the stress on the knee[30].

- Running form. Good running form has many benefits, but changing form tends to be difficult and can easily result in new injuries if done too quickly. I would recommend looking at Chi Running or the Pose Method, though personally I don't agree with their approach of pure forefoot running (your heal not touching the ground) and prefer a midfoot strike.

- Check for ITBS. ITBS produces pain to the outside of the knee, rather than under the kneecap. It's possible to have both kneecap pain and ITBS, so read Iliotibial band syndrome.

- Taping. The use of tape has been shown to be effective at reducing knee pain[31][32][33], by over 90% in one study[34]. One study used tape to pull the knee cap towards the midline of the body[35], others relied on evaluation to define the correct direction[32]. The most common method mentioned is 'McConnell taping'[33][32], and instructions can be found by Googling 'McConnell taping'.

- VMO Re-timing. If the firing of your VMO is delayed, it may be possible to correct this. Ideally, the correction uses a combination of training and down in EMG biofeedback device. These devices can be quite expensive, but it may be possible to detect the difference in timing between the VMO and the VL using your fingertips[12]. The goal should be retraining control rather than strengthening, with 200 repetitions per day (20x 10 reps) being required[12]. (I did find instructions for a DIY EMG.)In addition, it may be possible to mitigate the VMO timing problem with taping[31][33] (see below).

- Joint Supplements. The joint supplements glucosamine and chondroitin provide marginal benefit, but are considered safe, so they may be worth considering if you can justify the expense. Other supplements such as Omega 3 oils and Vitamin C/E may be worth considering. For more details, see Joint Supplements.

- Knee brace/sleeve/strap. A knee sleeve is a simple elastic wrap that goes around the knee, sometimes with a hole to avoid pressure on the kneecap. A knee brace usually provides hard plastic support in addition to the sleeve. The evidence supporting knee braces is limited[36][37], with many of the studies having poor quality[37]. One reasonable study showed improvement with a brace[38], but better quality studies showed no benefit[39][40][41]. There are even fewer studies for knee sleeves[42]. The only study on knee straps showed no benefit[39]. I found no indications of the long term effects or safety of knee braces, sleeves or straps. Based on the available evidence, the use of these approaches does not seem justified. I found no studies that looked at Compression Tights but they may act in a similar way to a knee sleeve and they have other benefits.

3 Anti-treatments

The following 'treatments' are not recommended.

- Quad resistance training. A common recommendation is to strengthen the quad muscles to improve the tracking of the kneecap, especially the VMO. However, resistance training of the quads puts extra strain on the kneecap and can cause a worsening of the symptoms[3]. Any strengthening of the quads should focus on the VMO.

- Surgery to correct mistracking. A study of knee pain indicated that this type of surgery has the second highest failure rate[3].

- NSAIDs. Using NSAIDs does not generally improve healing, can mask symptoms and is a cause of cartilage damage[22]. An animal study showed that Asprin resulted in greater cartilage degeneration[43]. More at NSAIDs and Running.

4 Surgery

Surgery for knee problems is a common treatment, but the research suggest is may not be worthwhile. While surgery and exercise seem to generally result in improved pain, function, and quality of life, it doesn't do better than a program of exercise. So far I've found no research supporting knee surgery, though most of the research I've found has been on meniscus tears.

- A 2012 study looked at 102 patients with a meniscus tear and compared surgery with strengthening and found no difference in terms of function or pain after two years[44]. Both groups reported a high degree of satisfaction with their treatment. The exercise group was given supervised training three times per week for three weeks, then a further eight weeks of unsupervised exercise. The exercise consisted of stretching the hamstrings and quads (1 min each), 3 x 10 reps of leg extensions, leg curls, half squats and full squats, plus 15 minutes of cycling. The squats were only for the last 3 of the 8 weeks, and all exercise was to be with some strain but almost pain free. There's no reason to believe this regime is optimal, but it's an interesting starting point.

- A 2013 study looked at with a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis in 351 subjects, with half randomly assigned to surgery, the others to physical therapy[45]. The study did not find any significant difference in functional improvement after 6 months. (30% of those assigned to physical therapy elected to have surgery before the 6 months were up.)

- A 2008 study found that 60% of subjects aged 50+ had meniscus tears[46]. The rate of meniscus tears was similar in patients with and without knee pain symptoms. What's not clear is that if you have a meniscus tear and you have knee pain, what's the chance of the two being unrelated? It seems quite possible from the data that you could have surgery for a meniscus tear that has nothing to do with your pain.

- A 2013 study looked at 96 subjects over five years after either surgery plus 2 months of exercise or just exercise for with degenerative meniscal tears[47]. No difference was found in the outcomes at the 2 and 5 year marks. It's worth noting that a third of the exercise only group still had disabling knee problems after the exercise therapy but they improved to the same level as the other subjects after surgery.

- A 2013 study comparing surgery with sham surgery for meniscus tears in 146 subjects over 12 months found no difference between the groups[48]. The subjects had knee pain for more than three months prior and had not responded to conservative treatment. Both groups improved over the 12 months, but there was no difference between the groups. This is one of the highest quality studies available, with some lengths taken to blind the subjects to their knowledge of the surgery or sham surgery.

- A 2007 study looked at 90 subjects with degenerative meniscal tears who were given either exercise or exercise plus surgery[49]. Both groups reported similar improvements in pain, knee function and quality of life. The exercise consisted of cycling, calf raises, leg press, stair walking, wobble board, jumping, stretching, and similar exercises to improve strength and balance.

- A small 2012 study of just 17 subjects compared surgery (n=8) with exercise (n=9) over three months and found no difference in pain levels or knee function[50]. However, the study did find that the surgery group had statistically more anxiety and depression.

- A 2014 analysis of the available research concluded that "There is moderate evidence to suggest that there is no benefit to arthroscopic meniscal débridement for degenerative meniscal tears"[51]. This review looked at seven trails (all of them noted here in more detail.)

- A 2013 study compared surgery with steroid injections for meniscus tears in 114 subjects[52]. They randomly received surgery or injections of betamethasone and lidocaine and evaluated at one month and one year. The study found only a marginal improvement in the surgery subjects over the steroid injection. However, given the evidence that surgery is no more effective than avoiding surgery, it might be better to say that steroid injections are worse than no surgery or surgery.

- There are indications that meniscus surgery may increase the risk for osteoarthritis, with the amount of meniscus removed tending to predict a higher osteoarthritis risk[53]. However, it's also possible that a meniscus tear without surgery also increases risk for osteoarthritis [54].

- A 2010 study of 121 young adults compared two treatment approach for acute, traumatic ACL injury[55]. One group received rehabilitation and surgery within 10 weeks (early group), the other group received rehabilitation with an option for surgery if required (delayed group). Only 40% of the delayed group underwent surgery, and both groups had similar success in terms of pain, quality of life, and difficulty in sports/recreational activities.

- A 2008 study of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis found that surgery had the same success rate as those who did not undergo surgery[56]. The study looked at 92 surgical patients and 86 controls over 2 years, with both groups receiving 12 weeks of physical and medical therapy, including exercise. The patients were told to continue the exercise unsupervised for the rest of the study. The evaluations at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months showed both groups improved a similar amount. This was a follow on to a 2002 study that had also found no difference in outcome from surgery or a placebo surgery[57],

5 References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries -- Taunton et al. 36 (2): 95 -- British Journal of Sports Medicine http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/36/2/95

- ↑ Runner's Knee (Patellofemoral Pain) - OrthoInfo - AAOS http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00382

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Patellofemoral Pain Current Concepts: An Overview : Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review http://journals.lww.com/sportsmedarthro/Abstract/2001/10000/Patellofemoral_Pain_Current_Concepts__An_Overview.2.aspx

- ↑ Ross H. Miller, W. Brent Edwards, Scott C. E. Brandon, Amy M. Morton, Kevin J. Deluzio, Why Don't Most Runners Get Knee Osteoarthritis? A Case for Per-Unit-Distance Loads, Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, volume 46, issue 3, 2014, pages 572–579, ISSN 0195-9131, doi 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000135

- ↑ THE ASSOCIATION OF KNEE INJURY AND OBESITY WITH UNILATERAL AND BILATERAL OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE KNEE http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/130/2/278.short

- ↑ Mechanisms of Selected Knee Injuries http://physicaltherapyjournal.com/content/60/12/1590.short

- ↑ Landing Pattern Modification to Improve Patellofemoral Pain in Runners: A Case Series - JOSPT – Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy http://www.jospt.org/issues/articleID.2653/article_detail.asp

- ↑ Minimalist Footwear http://antonkrupicka.blogspot.com/2007/10/minimalist-footwear.html

- ↑ Factors related to the incidence of running injuries. A review. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1615258

- ↑ M. B. Ryan, G. A. Valiant, K. McDonald, J. E. Taunton, The effect of three different levels of footwear stability on pain outcomes in women runners: a randomised control trial, British Journal of Sports Medicine, volume 45, issue 9, 2010, pages 715–721, ISSN 0306-3674, doi 10.1136/bjsm.2009.069849

- ↑ Response of joint structures to inactivity and to reloading after immobilization - Brandt - 2003 - Arthritis Care & Research - Wiley Online Library http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.11009/full

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Clinical classification of patellofemoral pain syndrome- guidelines for non-operative treatment, Erik Witvrouw, S. Werner, C. Mikkelsen, D. Van Tiggelen, L. Vanden Berghe, G. Cerulli

- ↑ Knee Injuries From Running at Runner's World.com http://www.runnersworld.com/article/0,7120,s6-241-285--7773-0,00.html

- ↑ The role of patellar alignment and tracking in vivo: The potential mechanism of patellofemoral pain syndrome http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1466853X11000162

- ↑ Role of the vastus medialis obliquus in repo... [Am J Sports Med. 2008] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18337358

- ↑ Vastus Medialis Obliquus Atrophy: Does It Exist in Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome? http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/04/12/0363546511401183

- ↑ http://rsi.aip.org/resource/1/rsinak/v82/i10/p105101_s1?isAuthorized=no

- ↑ The relative timing of VMO and VL in the aetiology of anterior knee pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/9/64

- ↑ The quadriceps function in patellofe... [Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1987] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3606363

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Hip strength and hip and knee kine... [J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18349475

- ↑ Greater Q angle may not be a ri... [Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21177007

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 ScienceDirect.com - The American Journal of Medicine - Profile and mechanisms of gastrointestinal and other side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002934399003654

- ↑ Gluteal muscle activation durin... [Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21388728

- ↑ The Effect of Running Shoes on Lower Extremity Joint Torques http://www.pmrjournal.org/article/S1934-1482(09)01367-7/fulltext

- ↑ Minimalism Case Studies | Running Times Magazine http://runningtimes.com/Article.aspx?ArticleID=22192

- ↑ Joint loading decreased by inexpensive and minimalist footwear in elderly women with knee osteoarthritis during stair descent - Sacco - 2012 - Arthritis Care & Research - Wiley Online Library http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.20690/abstract

- ↑ Application of wedged foot orthosis effectively reduces pain in runners with pronated foot: a randomized clinical study http://cre.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/07/16/0269215511411938.abstract

- ↑ The immediate effects of foot orthoses on fu... [Br J Sports Med. 2011] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20647297

- ↑ A randomised control trial of short term eff... [Br J Sports Med. 2012] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21930514

- ↑ Effect of footwear on the external knee adduction momen... [Knee. 2012] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21733696

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 The management of chondromalacia patellae: a long term solution http://svc019.wic048p.server-web.com/ajp/vol_32/4/AustJPhysiotherv32i4McConnell.pdf

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Effects of patella taping on patella po... [Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8231783

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 The effect of patellar taping on the onset of vast... [Phys Ther. 1998] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9442193

- ↑ Effect of taping the pat... [Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8536023

- ↑ Taping the patella medially: a new treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee joint? | BMJ http://www.bmj.com/content/308/6931/753.full

- ↑ Braces and orthoses for treating ... [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15674927

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Patellar taping and bracing for the treatment of chronic knee pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis - Warden - 2007 - Arthritis Care & Research - Wiley Online Library http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.23242/full

- ↑ The effect of bracing on patella alignm... [Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15235330

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 The efficacy of orthotics for anterior knee p... [Am J Knee Surg. 1997] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9051172

- ↑ Effectiveness of patellar bracing for treat... [Clin J Sport Med. 2005] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16003037

- ↑ A randomized trial of patellofemora... [Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21232620

- ↑ Clinical practice guidelines for rest ortho... [Joint Bone Spine. 2009] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19467901

- ↑ In vivo effect of aspirin on canine osteoarthritic cartilage - Palmoski - 2005 - Arthritis & Rheumatism - Wiley Online Library http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.1780260808/abstract

- ↑ J.-H. Yim, J.-K. Seon, E.-K. Song, J.-I. Choi, M.-C. Kim, K.-B. Lee, H.-Y. Seo, A Comparative Study of Meniscectomy and Nonoperative Treatment for Degenerative Horizontal Tears of the Medial Meniscus, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, volume 41, issue 7, 2013, pages 1565–1570, ISSN 0363-5465, doi 10.1177/0363546513488518

- ↑ Jeffrey N. Katz, Robert H. Brophy, Christine E. Chaisson, Leigh de Chaves, Brian J. Cole, Diane L. Dahm, Laurel A. Donnell-Fink, Ali Guermazi, Amanda K. Haas, Morgan H. Jones, Bruce A. Levy, Lisa A. Mandl, Scott D. Martin, Robert G. Marx, Anthony Miniaci, Matthew J. Matava, Joseph Palmisano, Emily K. Reinke, Brian E. Richardson, Benjamin N. Rome, Clare E. Safran-Norton, Debra J. Skoniecki, Daniel H. Solomon, Matthew V. Smith, Kurt P. Spindler, Michael J. Stuart, John Wright, Rick W. Wright, Elena Losina, Surgery versus Physical Therapy for a Meniscal Tear and Osteoarthritis, New England Journal of Medicine, volume 368, issue 18, 2013, pages 1675–1684, ISSN 0028-4793, doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1301408

- ↑ Martin Englund, Ali Guermazi, Daniel Gale, David J. Hunter, Piran Aliabadi, Margaret Clancy, David T. Felson, Incidental Meniscal Findings on Knee MRI in Middle-Aged and Elderly Persons, New England Journal of Medicine, volume 359, issue 11, 2008, pages 1108–1115, ISSN 0028-4793, doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0800777

- ↑ Sylvia V. Herrlin, Peter O. Wange, Gunilla Lapidus, Maria Hållander, Suzanne Werner, Lars Weidenhielm, Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up, Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, volume 21, issue 2, 2012, pages 358–364, ISSN 0942-2056, doi 10.1007/s00167-012-1960-3

- ↑ R. Sihvonen, M. Paavola, A. Malmivaara, A. Itälä, A. Joukainen, H. Nurmi, J. Kalske, TL. Järvinen, J. Nyrhinen, Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear., N Engl J Med, volume 369, issue 26, pages 2515-24, Dec 2013, doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1305189, PMID 24369076

- ↑ S. Herrlin, M. Hållander, P. Wange, L. Weidenhielm, S. Werner, Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial., Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, volume 15, issue 4, pages 393-401, Apr 2007, doi 10.1007/s00167-006-0243-2, PMID 17216272

- ↑ Håvard Østerås, Berit Østerås, Tom Arild Torstensen, Medical exercise therapy, and not arthroscopic surgery, resulted in decreased depression and anxiety in patients with degenerative meniscus injury, Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, volume 16, issue 4, 2012, pages 456–463, ISSN 13608592, doi 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.04.003

- ↑ M. Khan, N. Evaniew, A. Bedi, OR. Ayeni, M. Bhandari, Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative tears of the meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis., CMAJ, volume 186, issue 14, pages 1057-64, Oct 2014, doi 10.1503/cmaj.140433, PMID 25157057

- ↑ D. Vermesan, R. Prejbeanu, S. Laitin, G. Damian, B. Deleanu, A. Abbinante, P. Flace, R. Cagiano, Arthroscopic debridement compared to intra-articular steroids in treating degenerative medial meniscal tears., Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, volume 17, issue 23, pages 3192-6, Dec 2013, PMID 24338461

- ↑ R. Papalia, A. Del Buono, L. Osti, V. Denaro, N. Maffulli, Meniscectomy as a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review, British Medical Bulletin, volume 99, issue 1, 2011, pages 89–106, ISSN 0007-1420, doi 10.1093/bmb/ldq043

- ↑ Martin Englund, Ali Guermazi, Frank W. Roemer, Piran Aliabadi, Mei Yang, Cora E. Lewis, James Torner, Michael C. Nevitt, Burton Sack, David T. Felson, Meniscal tear in knees without surgery and the development of radiographic osteoarthritis among middle-aged and elderly persons: The multicenter osteoarthritis study, Arthritis & Rheumatism, volume 60, issue 3, 2009, pages 831–839, ISSN 00043591, doi 10.1002/art.24383

- ↑ Richard B. Frobell, Ewa M. Roos, Harald P. Roos, Jonas Ranstam, L. Stefan Lohmander, A Randomized Trial of Treatment for Acute Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears, New England Journal of Medicine, volume 363, issue 4, 2010, pages 331–342, ISSN 0028-4793, doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797

- ↑ Alexandra Kirkley, Trevor B. Birmingham, Robert B. Litchfield, J. Robert Giffin, Kevin R. Willits, Cindy J. Wong, Brian G. Feagan, Allan Donner, Sharon H. Griffin, Linda M. D'Ascanio, Janet E. Pope, Peter J. Fowler, A Randomized Trial of Arthroscopic Surgery for Osteoarthritis of the Knee, New England Journal of Medicine, volume 359, issue 11, 2008, pages 1097–1107, ISSN 0028-4793, doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0708333

- ↑ J. Bruce Moseley, Kimberly O'Malley, Nancy J. Petersen, Terri J. Menke, Baruch A. Brody, David H. Kuykendall, John C. Hollingsworth, Carol M. Ashton, Nelda P. Wray, A Controlled Trial of Arthroscopic Surgery for Osteoarthritis of the Knee, New England Journal of Medicine, volume 347, issue 2, 2002, pages 81–88, ISSN 0028-4793, doi 10.1056/NEJMoa013259