Difference between revisions of "NSAIDs and Running"

User:Fellrnr (User talk:Fellrnr | contribs) m (→NSAIDs and Acute kidney failure) |

User:Fellrnr (User talk:Fellrnr | contribs) |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

=NSAIDs for Pain Reduction= | =NSAIDs for Pain Reduction= | ||

The primary purpose of NSAIDs is generally for reducing pain, and they are remarkably effective at achieving this. If you need a painkiller, acetaminophen is probably a better choice than ibuprofen, though be careful as it's easy to overdose on Acetaminophen (see below). Acetaminophen has limited anti-inflammatory properties, so it shouldn't impair healing as much as ibuprofen, but it is still good as a painkiller. Combining acetaminophen or other NSAIDs with [[Caffeine]] further improves their painkilling effectiveness. After a major race I can sometimes have so much leg pain that I can't [[Zeo Sleep Monitor|sleep]] and a little acetaminophen can make all the difference. While the acetaminophen may impair healing somewhat I believe the trade-off in improved [[Zeo Sleep Monitor|sleep]] is worthwhile. After all, the lack of [[Zeo Sleep Monitor|sleep]] itself will impair healing, so it's a reasonable compromise. | The primary purpose of NSAIDs is generally for reducing pain, and they are remarkably effective at achieving this. If you need a painkiller, acetaminophen is probably a better choice than ibuprofen, though be careful as it's easy to overdose on Acetaminophen (see below). Acetaminophen has limited anti-inflammatory properties, so it shouldn't impair healing as much as ibuprofen, but it is still good as a painkiller. Combining acetaminophen or other NSAIDs with [[Caffeine]] further improves their painkilling effectiveness. After a major race I can sometimes have so much leg pain that I can't [[Zeo Sleep Monitor|sleep]] and a little acetaminophen can make all the difference. While the acetaminophen may impair healing somewhat I believe the trade-off in improved [[Zeo Sleep Monitor|sleep]] is worthwhile. After all, the lack of [[Zeo Sleep Monitor|sleep]] itself will impair healing, so it's a reasonable compromise. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

=NSAIDs and DOMS= | =NSAIDs and DOMS= | ||

| − | + | Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) generally occurs between 24 and 72 hours after unusual or severe exercise, such as racing a marathon or downhill running. The use of NSAIDs to prevent or treat DOMS has been widely researched, with somewhat mixed results. Even scholarly reviews of the research have differing conclusions<ref name="Cheung-2003"/> <ref name="Smith-1992"/> <ref name="Baldwin Lanier-2003"/><ref name="Howatson-2008"/>. My conclusions based on the available research are: | |

| + | * The most common NSAIDs (Ibuprofen, Acetaminophen (Paracetamol), and Aspirin) are unlikely to help with DOMS. | ||

| + | * There is some evidence that Naproxen may be more effective than the common NSAIDs. There is not enough evidence to reach a conclusion on Diclofenac, Codeine, Rofecoxib, Ketoprofen, or Bromelain. | ||

| + | * If an NSAID is taken for DOMS, it should probably be taken immediately after the damaging exercise rather than waiting until the soreness develops. | ||

| + | * It seems likely that taking an NSAID for DOMS will reduce the muscular growth that would normally occur as part of the recovery. | ||

| + | ** In one study, rabbits treated with flurbiprofen after DOMS inducing exercise regained more strength after 3-7 days, but between days 7 and 28 days the treated rabbits became weaker while the controls became stronger<ref name="Mishra-1995"/>. This is only one study, and on animals, but it is rather troubling as none of the human studies look at the results over this time period. | ||

| + | =A Summary of the Research on NSAIDs and DOMS= | ||

| + | The table below summarizes the research I located on the effect of NSAIDs on DOMS in humans. I've only considered the primary DOMS markers of soreness (pain) and weakness, rather than including things like blood enzymes. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | !NSAID!!Soreness!!Weakness | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Ibuprofen | ||

| + | |7xNo<ref name="Grossman-1995"/><ref name="Pizza-1999"/><ref name="RahnamaRahmani-Nia2005"/> <ref name="KrentzQuest2008"/><ref name="Arendt-NielsenWeidner2007"/><ref name="Donnelly-1990"/><ref name="Stone-2002"/> | ||

| + | 2xYes<ref name="Hasson-1993"/><ref name="pmid12580656"/> | ||

| + | |8xNo<ref name="Grossman-1995"/><ref name="Pizza-1999"/><ref name="RahnamaRahmani-Nia2005"/> <ref name="KrentzQuest2008"/><ref name="Arendt-NielsenWeidner2007"/><ref name="Donnelly-1990"/><ref name="pmid12580656"/><ref name="Stone-2002"/> | ||

| + | 1xMaybe<ref name="Hasson-1993"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) | ||

| + | |2xNo<ref name="Barlas-2000"/><ref name="SmithGeorge1995"/> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Aspirin | ||

| + | |2xYes<ref name="Riasata-2010"/><ref name="Francis-1987"/> | ||

| + | 2xNo<ref name="Barlas-2000"/><ref name="SmithGeorge1995"/> | ||

| + | |2xNo<ref name="Riasata-2010"/><ref name="Francis-1987"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Naproxen | ||

| + | |4xYes<ref name="Dudley-1997"/><ref name="Baldwin-2001"/><ref name="Lecomte-1998"/><ref name="journals.ut.ac.ir"/> | ||

| + | 1xNo<ref name="Bourgeois-1999"/> | ||

| + | |3xYes<ref name="Dudley-1997"/><ref name="Baldwin-2001"/><ref name="Lecomte-1998"/> | ||

| + | 1xNo<ref name="Bourgeois-1999"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Diclofenac | ||

| + | |Possible slight reduction<ref name="DonnellyMcCormick1988"/> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Codeine | ||

| + | |1xNo<ref name="Barlas-2000"/> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Rofecoxib | ||

| + | |1xNo<ref name="LoramMitchell2005"/> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Ketoprofen | ||

| + | |1xYes<ref name="Sayers-2001"/> | ||

| + | |1xYes<ref name="Sayers-2001"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Bromelain | ||

| + | |1xNo<ref name="Stone-2002"/> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

=NSAIDs and Intestinal Damage= | =NSAIDs and Intestinal Damage= | ||

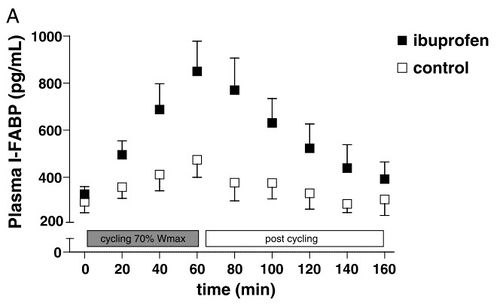

As little as one hour of intense cycling can result in indications of small intestinal damage<ref name="van Wijck-2011"/>. This is believed to be due to the redirection of blood away from the digestive system and towards the active muscles. These markers are significantly higher if 400mg ibuprofen (the standard single adult dose) is taken before the exercise<ref name="VAN Wijck-2012"/>. The marker used is Plasma Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein which is an early marker of intestinal necrosis<ref name="Vermeulen Windsant-2012"/>. | As little as one hour of intense cycling can result in indications of small intestinal damage<ref name="van Wijck-2011"/>. This is believed to be due to the redirection of blood away from the digestive system and towards the active muscles. These markers are significantly higher if 400mg ibuprofen (the standard single adult dose) is taken before the exercise<ref name="VAN Wijck-2012"/>. The marker used is Plasma Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein which is an early marker of intestinal necrosis<ref name="Vermeulen Windsant-2012"/>. | ||

| Line 88: | Line 143: | ||

<ref name="van Wijck-2011"> {{Cite journal | last1 = van Wijck | first1 = K. | last2 = Lenaerts | first2 = K. | last3 = van Loon | first3 = LJ. | last4 = Peters | first4 = WH. | last5 = Buurman | first5 = WA. | last6 = Dejong | first6 = CH. | title = Exercise-induced splanchnic hypoperfusion results in gut dysfunction in healthy men. | journal = PLoS One | volume = 6 | issue = 7 | pages = e22366 | month = | year = 2011 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0022366 | PMID = 21811592 }}</ref> | <ref name="van Wijck-2011"> {{Cite journal | last1 = van Wijck | first1 = K. | last2 = Lenaerts | first2 = K. | last3 = van Loon | first3 = LJ. | last4 = Peters | first4 = WH. | last5 = Buurman | first5 = WA. | last6 = Dejong | first6 = CH. | title = Exercise-induced splanchnic hypoperfusion results in gut dysfunction in healthy men. | journal = PLoS One | volume = 6 | issue = 7 | pages = e22366 | month = | year = 2011 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0022366 | PMID = 21811592 }}</ref> | ||

<ref name="Vermeulen Windsant-2012"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Vermeulen Windsant | first1 = IC. | last2 = Hellenthal | first2 = FA. | last3 = Derikx | first3 = JP. | last4 = Prins | first4 = MH. | last5 = Buurman | first5 = WA. | last6 = Jacobs | first6 = MJ. | last7 = Schurink | first7 = GW. | title = Circulating intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as an early marker of intestinal necrosis after aortic surgery: a prospective observational cohort study. | journal = Ann Surg | volume = 255 | issue = 4 | pages = 796-803 | month = Apr | year = 2012 | doi = 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b1e16 | PMID = 22367448 }}</ref> | <ref name="Vermeulen Windsant-2012"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Vermeulen Windsant | first1 = IC. | last2 = Hellenthal | first2 = FA. | last3 = Derikx | first3 = JP. | last4 = Prins | first4 = MH. | last5 = Buurman | first5 = WA. | last6 = Jacobs | first6 = MJ. | last7 = Schurink | first7 = GW. | title = Circulating intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as an early marker of intestinal necrosis after aortic surgery: a prospective observational cohort study. | journal = Ann Surg | volume = 255 | issue = 4 | pages = 796-803 | month = Apr | year = 2012 | doi = 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b1e16 | PMID = 22367448 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Riasata-2010">Riasati et al.: Aspirin and delayed onset muscle soreness ASPIRIN MAY BE AN EFFECTIVE TREATMENT FOR EXERCISE- INDUCED MUSCLE SORENESS | ResearchGate http://www.researchgate.net/publication/228091056_Riasati_et_al._Aspirin_and_delayed_onset_muscle_soreness_ASPIRIN_MAY_BE_AN_EFFECTIVE_TREATMENT_FOR_EXERCISE-_INDUCED_MUSCLE_SORENESS </ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Francis-1987"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Francis | first1 = KT. | last2 = Hoobler | first2 = T. | title = Effects of aspirin on delayed muscle soreness. | journal = J Sports Med Phys Fitness | volume = 27 | issue = 3 | pages = 333-7 | month = Sep | year = 1987 | doi = | PMID = 3431117 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Donnelly-1990"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Donnelly | first1 = AE. | last2 = Maughan | first2 = RJ. | last3 = Whiting | first3 = PH. | title = Effects of ibuprofen on exercise-induced muscle soreness and indices of muscle damage. | journal = Br J Sports Med | volume = 24 | issue = 3 | pages = 191-5 | month = Sep | year = 1990 | doi = | PMID = 2078806 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="DonnellyMcCormick1988">{{cite journal|last1=Donnelly|first1=A E|last2=McCormick|first2=K|last3=Maughan|first3=R J|last4=Whiting|first4=P H|last5=Clarkson|first5=P M|title=Effects of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug on delayed onset muscle soreness and indices of damage.|journal=British Journal of Sports Medicine|volume=22|issue=1|year=1988|pages=35–38|issn=0306-3674|doi=10.1136/bjsm.22.1.35}}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Hasson-1993"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Hasson | first1 = SM. | last2 = Daniels | first2 = JC. | last3 = Divine | first3 = JG. | last4 = Niebuhr | first4 = BR. | last5 = Richmond | first5 = S. | last6 = Stein | first6 = PG. | last7 = Williams | first7 = JH. | title = Effect of ibuprofen use on muscle soreness, damage, and performance: a preliminary investigation. | journal = Med Sci Sports Exerc | volume = 25 | issue = 1 | pages = 9-17 | month = Jan | year = 1993 | doi = | PMID = 8423760 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Grossman-1995">Effect of Ibuprofen Use on Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness of the Elbow Flexors http://journals.humankinetics.com/jsr-back-issues/jsrvolume4issue4november/effectofibuprofenuseondelayedonsetmusclesorenessoftheelbowflexors </ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Dudley-1997"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Dudley | first1 = GA. | last2 = Czerkawski | first2 = J. | last3 = Meinrod | first3 = A. | last4 = Gillis | first4 = G. | last5 = Baldwin | first5 = A. | last6 = Scarpone | first6 = M. | title = Efficacy of naproxen sodium for exercise-induced dysfunction muscle injury and soreness. | journal = Clin J Sport Med | volume = 7 | issue = 1 | pages = 3-10 | month = Jan | year = 1997 | doi = | PMID = 9117523 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Barlas-2000"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Barlas | first1 = P. | last2 = Craig | first2 = JA. | last3 = Robinson | first3 = J. | last4 = Walsh | first4 = DM. | last5 = Baxter | first5 = GD. | last6 = Allen | first6 = JM. | title = Managing delayed-onset muscle soreness: lack of effect of selected oral systemic analgesics. | journal = Arch Phys Med Rehabil | volume = 81 | issue = 7 | pages = 966-72 | month = Jul | year = 2000 | doi = 10.1053/apmr.2000.6277 | PMID = 10896014 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Pizza-1999"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Pizza | first1 = FX. | last2 = Cavender | first2 = D. | last3 = Stockard | first3 = A. | last4 = Baylies | first4 = H. | last5 = Beighle | first5 = A. | title = Anti-inflammatory doses of ibuprofen: effect on neutrophils and exercise-induced muscle injury. | journal = Int J Sports Med | volume = 20 | issue = 2 | pages = 98-102 | month = Feb | year = 1999 | doi = 10.1055/s-2007-971100 | PMID = 10190769 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="SmithGeorge1995">{{cite journal|last1=Smith|first1=Lucille|last2=George|first2=Robert|last3=Chenier|first3=Thomas|last4=McCammon|first4=Michael|last5=Houmard|first5=Joseph|last6=Israel|first6=Richard|last7=Hoppmann|first7=R. A.|last8=Smith|first8=Susan|title=Do over-the-counter analgesics reduce delayed onset muscle soreness and serum creatine kinase values?|journal=Research in Sports Medicine|volume=6|issue=2|year=1995|pages=81–88|issn=1543-8627|doi=10.1080/15438629509512039}}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Baldwin-2001"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Baldwin | first1 = AC. | last2 = Stevenson | first2 = SW. | last3 = Dudley | first3 = GA. | title = Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy after eccentric exercise in healthy older individuals. | journal = J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci | volume = 56 | issue = 8 | pages = M510-3 | month = Aug | year = 2001 | doi = | PMID = 11487604 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="pmid12580656">{{cite journal| author=Tokmakidis SP, Kokkinidis EA, Smilios I, Douda H| title=The effects of ibuprofen on delayed muscle soreness and muscular performance after eccentric exercise. | journal=J Strength Cond Res | year= 2003 | volume= 17 | issue= 1 | pages= 53-9 | pmid=12580656 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=12580656 }} </ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Stone-2002"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Stone | first1 = MB. | last2 = Merrick | first2 = MA. | last3 = Ingersoll | first3 = CD. | last4 = Edwards | first4 = JE. | title = Preliminary comparison of bromelain and Ibuprofen for delayed onset muscle soreness management. | journal = Clin J Sport Med | volume = 12 | issue = 6 | pages = 373-8 | month = Nov | year = 2002 | doi = | PMID = 12466693 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="RahnamaRahmani-Nia2005">{{cite journal|last1=Rahnama|first1=N|last2=Rahmani-Nia|first2=F|last3=Ebrahim|first3=K|title=The isolated and combined effects of selected physical activity and ibuprofen on delayed-onset muscle soreness|journal=Journal of Sports Sciences|volume=23|issue=8|year=2005|pages=843–850|issn=0264-0414|doi=10.1080/02640410400021989}}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="KrentzQuest2008">{{cite journal|last1=Krentz|first1=Joel R.|last2=Quest|first2=Braden|last3=Farthing|first3=Jonathan P.|last4=Quest|first4=Dale W.|last5=Chilibeck|first5=Philip D.|title=The effects of ibuprofen on muscle hypertrophy, strength, and soreness during resistance training|journal=Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism|volume=33|issue=3|year=2008|pages=470–475|issn=1715-5312|doi=10.1139/H08-019}}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="HyldahlKeadle2010">{{cite journal|last1=Hyldahl|first1=Robert D.|last2=Keadle|first2=Justin|last3=Rouzier|first3=Pierre A.|last4=Pearl|first4=Dennis|last5=Clarkson|first5=Priscilla M.|title=Effects of Ibuprofen Topical Gel on Muscle Soreness|journal=Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise|volume=42|issue=3|year=2010|pages=614–621|issn=0195-9131|doi=10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b95db2}}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Arendt-NielsenWeidner2007">{{cite journal|last1=Arendt-Nielsen|first1=Lars|last2=Weidner|first2=Morten|last3=Bartholin|first3=Dorte|last4=Rosetzsky|first4=Allan|title=A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo Controlled Parallel Group Study Evaluating the Effects of Ibuprofen and Glucosamine Sulfate on Exercise Induced Muscle Soreness|journal=Journal Of Musculoskeletal Pain|volume=15|issue=1|year=2007|pages=21–28|issn=1058-2452|doi=10.1300/J094v15n01_04}}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Trappe-2011"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Trappe | first1 = TA. | last2 = Carroll | first2 = CC. | last3 = Dickinson | first3 = JM. | last4 = LeMoine | first4 = JK. | last5 = Haus | first5 = JM. | last6 = Sullivan | first6 = BE. | last7 = Lee | first7 = JD. | last8 = Jemiolo | first8 = B. | last9 = Weinheimer | first9 = EM. | title = Influence of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance exercise in older adults. | journal = Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol | volume = 300 | issue = 3 | pages = R655-62 | month = Mar | year = 2011 | doi = 10.1152/ajpregu.00611.2010 | PMID = 21160058 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="LoramMitchell2005">{{cite journal|last1=Loram|first1=L.C.|last2=Mitchell|first2=D.|last3=Fuller|first3=A.|title=Rofecoxib and tramadol do not attenuate delayed-onset muscle soreness or ischaemic pain in human volunteers|journal=Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology|volume=83|issue=12|year=2005|pages=1137–1145|issn=0008-4212|doi=10.1139/y05-113}}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Howatson-2008"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Howatson | first1 = G. | last2 = van Someren | first2 = KA. | title = The prevention and treatment of exercise-induced muscle damage. | journal = Sports Med | volume = 38 | issue = 6 | pages = 483-503 | month = | year = 2008 | doi = | PMID = 18489195 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Lecomte-1998"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Lecomte | first1 = JM. | last2 = Lacroix | first2 = VJ. | last3 = Montgomery | first3 = DL. | title = A randomized controlled trial of the effect of naproxen on delayed onset muscle soreness and muscle strength. | journal = Clin J Sport Med | volume = 8 | issue = 2 | pages = 82-7 | month = Apr | year = 1998 | doi = | PMID = 9641434 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Mishra-1995"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Mishra | first1 = DK. | last2 = Fridén | first2 = J. | last3 = Schmitz | first3 = MC. | last4 = Lieber | first4 = RL. | title = Anti-inflammatory medication after muscle injury. A treatment resulting in short-term improvement but subsequent loss of muscle function. | journal = J Bone Joint Surg Am | volume = 77 | issue = 10 | pages = 1510-9 | month = Oct | year = 1995 | doi = | PMID = 7593059 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Sayers-2001"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Sayers | first1 = SP. | last2 = Knight | first2 = CA. | last3 = Clarkson | first3 = PM. | last4 = Van Wegen | first4 = EH. | last5 = Kamen | first5 = G. | title = Effect of ketoprofen on muscle function and sEMG activity after eccentric exercise. | journal = Med Sci Sports Exerc | volume = 33 | issue = 5 | pages = 702-10 | month = May | year = 2001 | doi = | PMID = 11323536 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Trappe-2002"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Trappe | first1 = TA. | last2 = White | first2 = F. | last3 = Lambert | first3 = CP. | last4 = Cesar | first4 = D. | last5 = Hellerstein | first5 = M. | last6 = Evans | first6 = WJ. | title = Effect of ibuprofen and acetaminophen on postexercise muscle protein synthesis. | journal = Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab | volume = 282 | issue = 3 | pages = E551-6 | month = Mar | year = 2002 | doi = 10.1152/ajpendo.00352.2001 | PMID = 11832356 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Bourgeois-1999"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Bourgeois | first1 = J. | last2 = MacDougall | first2 = D. | last3 = MacDonald | first3 = J. | last4 = Tarnopolsky | first4 = M. | title = Naproxen does not alter indices of muscle damage in resistance-exercise trained men. | journal = Med Sci Sports Exerc | volume = 31 | issue = 1 | pages = 4-9 | month = Jan | year = 1999 | doi = | PMID = 9927002 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="journals.ut.ac.ir"> {{Cite web | last = | first = | title = The Effect of Taking Naproxen Drug on the Level of Perceived Pain and Changes of CPK Serum after Eccentric Exercise - Harakat Volume: 37, Issue:| url = http://journals.ut.ac.ir/page/article-frame.html?langId=en&articleId=1003701| publisher = | date = | accessdate = 3 January 2013}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

</references> | </references> | ||

Revision as of 06:40, 4 January 2013

NSAIDs are Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs, the most common are Ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), Acetaminophen/Paracetamol (Tylenol, aspirin-free Anacin, Excedrin, and numerous cold medicines) and Aspirin. They work by inhibiting a particular enzyme (Cyclooxygenase) which reduces pain, fever and inflammation. NSAIDs are generally bad for runners, impairing healing, masking symptoms, interfering with hydration and in extreme situations can be life threatening. Ibuprofen use is so common among runners that it is sometimes called "Vitamin I"[1].

Contents

- 1 NSAIDs and Healing

- 2 NSAIDs and Acute kidney failure

- 3 NSAIDs and Hyponatremia

- 4 NSAIDs and Sickness

- 5 NSAIDs for Pain Reduction

- 6 NSAIDs and DOMS

- 7 A Summary of the Research on NSAIDs and DOMS

- 8 NSAIDs and Intestinal Damage

- 9 NSAIDs and Racing

- 10 Longer Term NSAID usage

- 11 Acetaminophen Overdose Danger (AKA Paracetamol, Tylenol)

- 12 Tangent - Is Acetaminophen really an NSAID?

- 13 References

1 NSAIDs and Healing

The inflammation response of our bodies is a key part of the healing process. Using NSAIDs to reduce the inflammation has been shown to impair healing in different tissue types:

- Muscles. [2]. A 2001 study showed that Ibuprofen and Acetaminiaphen reduce muscle growth after eccentric exercise. Another study[3] on muscle damage and NSAIDs showed impaired recovery in the early stages of healing. There was some increased protein synthesis with NSAIDs in latter stages of healing, but the muscles were still weaker 28 days after injury. Other studies[4][5] have shown that four days after injury, NSAIDs resulted in very little muscle regeneration compared with no drugs.

- Tendons. A primate study[6] showed "a marked decrease in the breaking strength of tendons at four and six weeks in the ibuprofen-treated animals". Another animal study[7] showed treated tendons were 32% weaker than their untested counterparts.

- Bone-Tendon Junctions. An animal study[8] of rotator cuff injuries shows that NSAID usage resulted in injuries that did not heal, and those that did heal were weaker than those without NSAID. To quote from the study "Given that NSAID administration was discontinued after 14 days yet affected load-to-failure eight weeks following repair, it appears that inhibition of the early events in the inflammatory cascade has a lasting negative effect on tendon-to-bone healing," Dr. Rodeo said.

- Cartilage. NSAIDs have been shown[9] to impair the healing of bone and cartilage in rabbits.

- Bone fractures. Tests on rats shows that a NSAID (Celecoxib) in the early stages of bone healing impaired healing, producing a weaker repair.[10] A study [11] in 2004 declared " Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs continue to be prescribed as analgesics for patients with healing fractures even though these drugs diminish bone formation, healing, and remodeling".

1.1 Counterpoint

While there is extensive experimental evidence for NSAIDs impairing healing, there are also some studies that show no change with NSAID use, and a few that indicated improved healing. For instance, one study[12] showed that using an NSAID for 6 days after injury resulted in a 42% increased ligament strength at day 14, though there was no change by day 21. Another study[13] showed that an NSAID did not change ligament healing, but did improve the strength of the uninjured ligaments. However, my reading indicates that the preponderance of evidence shows NSAIDs impair healing.

1.2 Ice, Inflammation and Healing

If NSAIDs are bad for healing, should we treat with ice? So far I have found no definitive studies, but ice has a difference mechanism of action from NSAIDs. By cooling the tissues, ice temporarily reduces inflammation, thereby flushing the wound. It does not directly impact any of the body's enzymes or other processes. If applied for a longer period of time, ice will produce a periodic increase in blood supply that creates a further flushing effect. I have found that ice can produce dramatic improvements in healing speed. See Cryotherapy - Ice for Healing for more details.

2 NSAIDs and Acute kidney failure

Kidney failure while running is extremely rare, and seems to require multiple factors to come together. Looking at the Comrades Marathon, a 90 Km/56 Mile ultramarathon in South Africa, there have only been 19 cases of kidney failure between 1969 and 1986, it even though thousands of people participate each year[14]. The following are considered factors in acute kidney failure related to running.

- Dehydration. Exercise reduces blood flow to the kidneys and dehydration makes this worse.

- NSAIDs. NSAIDs also reduce blood flow to the kidneys[15]. NSAIDs reduce prostaglandin production, and prostaglandins are vital to maintaining blood flow to the kidneys. While NSAIDs are considered safe drugs, NSAIDs are associated with a relatively high incidence of adverse drug reactions involving the kidneys. Generally NSAID side effects are restricted to individuals with predisposition to kidney problems, so extra care should be taken if you have a history of kidney problems. However, athletes push their bodies to extremes, so what applies to the general population may not be valid for runners. One runner was told[16] by doctors that 2400mg Ibuprofen in an ultramarathon was a contributing factor to his kidney failure.

- Rhabdomyolysis. All strenuous exercise causes some muscle damage, but this is generally resolved without a problem. However large amounts of a protein called myoglobin from damaged muscle can cause a condition called rhabdomyolysis (AKA 'rhabdo'). While serious rhabdomyolysis is rare, it is worth understanding one key symptom, which is low volume, dark urine, often likened to 'coca-cola'. The other symptoms include severe, incapacitating muscle pain and elevated levels of creatine kinase (CK) in the blood (which requires a specialist test). Some individuals[17] have a genetic condition that makes rhabdomyolysis possible after relatively moderate exercise. Rhabdomyolysis is also more likely after eccentric exercise, such as Downhill Running.

- Sickness. A viral or bacterial infection is often a factor in exercise related kidney failure.

Looking at the analysis[15] of nine cases of continued kidney failure in Comrades Marathon, seven had taken NSAIDs, four may have had a viral or bacterial infection. The combination of dehydration, rhabdomyolysis, infection and NSAIDs are a perfect storm for the kidneys.

3 NSAIDs and Hyponatremia

The kidneys are responsible for removing excess fluid from the blood as well as excreting or withholding sodium. If kidney function is compromised, then this can result in Hyponatremia, which can be fatal. Some studies[18][19][20] have shown a correlation between NSAID use in races and Hyponatremia, but others[21][22] have not. Using NSAIDs when hydration is a concern increases the risk of problems occuring.

4 NSAIDs and Sickness

Because a bacterial or viral infection puts more stress on the body, including the kidneys, taking NSAIDs and continuing to run increases your risk of complications. If the sickness is too bad to run without NSAIDs, you probably shouldn't run.

5 NSAIDs for Pain Reduction

The primary purpose of NSAIDs is generally for reducing pain, and they are remarkably effective at achieving this. If you need a painkiller, acetaminophen is probably a better choice than ibuprofen, though be careful as it's easy to overdose on Acetaminophen (see below). Acetaminophen has limited anti-inflammatory properties, so it shouldn't impair healing as much as ibuprofen, but it is still good as a painkiller. Combining acetaminophen or other NSAIDs with Caffeine further improves their painkilling effectiveness. After a major race I can sometimes have so much leg pain that I can't sleep and a little acetaminophen can make all the difference. While the acetaminophen may impair healing somewhat I believe the trade-off in improved sleep is worthwhile. After all, the lack of sleep itself will impair healing, so it's a reasonable compromise.

6 NSAIDs and DOMS

Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) generally occurs between 24 and 72 hours after unusual or severe exercise, such as racing a marathon or downhill running. The use of NSAIDs to prevent or treat DOMS has been widely researched, with somewhat mixed results. Even scholarly reviews of the research have differing conclusions[23] [24] [25][26]. My conclusions based on the available research are:

- The most common NSAIDs (Ibuprofen, Acetaminophen (Paracetamol), and Aspirin) are unlikely to help with DOMS.

- There is some evidence that Naproxen may be more effective than the common NSAIDs. There is not enough evidence to reach a conclusion on Diclofenac, Codeine, Rofecoxib, Ketoprofen, or Bromelain.

- If an NSAID is taken for DOMS, it should probably be taken immediately after the damaging exercise rather than waiting until the soreness develops.

- It seems likely that taking an NSAID for DOMS will reduce the muscular growth that would normally occur as part of the recovery.

- In one study, rabbits treated with flurbiprofen after DOMS inducing exercise regained more strength after 3-7 days, but between days 7 and 28 days the treated rabbits became weaker while the controls became stronger[27]. This is only one study, and on animals, but it is rather troubling as none of the human studies look at the results over this time period.

7 A Summary of the Research on NSAIDs and DOMS

The table below summarizes the research I located on the effect of NSAIDs on DOMS in humans. I've only considered the primary DOMS markers of soreness (pain) and weakness, rather than including things like blood enzymes.

| NSAID | Soreness | Weakness |

|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen | 7xNo[28][29][30] [31][32][33][34] | 8xNo[28][29][30] [31][32][33][36][34]

1xMaybe[35] |

| Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) | 2xNo[37][38] | |

| Aspirin | 2xYes[39][40] | 2xNo[39][40] |

| Naproxen | 4xYes[41][42][43][44]

1xNo[45] |

3xYes[41][42][43]

1xNo[45] |

| Diclofenac | Possible slight reduction[46] | |

| Codeine | 1xNo[37] | |

| Rofecoxib | 1xNo[47] | |

| Ketoprofen | 1xYes[48] | 1xYes[48] |

| Bromelain | 1xNo[34] |

8 NSAIDs and Intestinal Damage

As little as one hour of intense cycling can result in indications of small intestinal damage[49]. This is believed to be due to the redirection of blood away from the digestive system and towards the active muscles. These markers are significantly higher if 400mg ibuprofen (the standard single adult dose) is taken before the exercise[50]. The marker used is Plasma Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein which is an early marker of intestinal necrosis[51].

9 NSAIDs and Racing

Taking NSAIDs in ultramarathon events can improve performance by reducing pain and acute inflammation, but doing so represents a significant risk. There is some evidence[52] [53] that many runners taking NSAIDs have the same level of pain and greater damage markers compared with non-users. This may be because the runners push themselves to a similar level of pain, with the NSAIDs allowing them to do more damage.

- It seems likely that NSAIDs will increase the risk of injury rather than reducing it, as the symptoms of damage will be masked.

- The most common NSAID for racing seems to be ibuprofen. I've not seen any evidence of the relative effectiveness of different NSAIDs on performance.

- It is better to take liquid ibuprofen than tablets or capsules. The tablets and capsules take longer to dissolve and if you have a digestive problem they may not be fully absorbed. You can chew the tablets, but this is unpleasant and ibuprofen can irritate your mouth and throat slightly, so the liquid form is best. It's obviously harder to transport, but you can fill an old film canister with a dose.

- Before an ultramarathon race, you should think through under what circumstances you will consider using NSAIDs and what dosage. Make sure your crew knows that you're taking NSAIDs in case anything happens.

- Extra care should be taken when NSAIDs are used in combination with dehydration, sickness or running the causes serious muscle damage.

- Taking NSAIDs in marathon or shorter races is probably ineffective as the level of damage seen is not as great as in ultramarathon events.

- If you need NSAIDs to start a race, you probably should not compete.

10 Longer Term NSAID usage

Using NSAIDs for longer periods of time can lead to serious health problems and can be fatal. I have a running friend who had a bleeding ulcer from using Ibuprofen, which is a known[54] side effect. The likelihood of a bleeding or perforated ulcer goes up with time, from 1% after 3-6 months, to 2-4% after 12 months. 35% of long term Ibuprofen users get an ulcer[55], which are grim odds.

11 Acetaminophen Overdose Danger (AKA Paracetamol, Tylenol)

Acetaminophen does not have the same risk of ulcers, but it is linked to liver damage, especially in those who drink alcohol. Acetaminophen is the leading cause of acute liver failure[56][57]. There are concerns[58] that even the standard dose can cause changes in liver function. Acetaminophen can cause delayed symptoms[57], with people seeking medical help up to 5 days after the overdose (20% < 12 hours, 35% 12-24 hours, 45% 24 hours+). Overdoses of Acetaminophen can be caused by taking slightly too much over several days, with the toxicity building up[57]. This problem is again exacerbated by those taking alcohol with Acetaminophen[57]. (One factor that increases the risk is that some common medications, such as cold remedies, include Acetaminophen. If people do not add in the dose of Acetaminophen from these other sources, it is easy to unwittingly exceed the safe dosage.)

12 Tangent - Is Acetaminophen really an NSAID?

There are differing opinions around the classification of Acetaminophen as an NSAID with some resources[59] stating it is not an NSAID. While Acetaminophen has limited anti-inflammatory properties, it shares the same mechanism of action with most NSAIDs of inhibiting the COX enzyme and the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. It is therefore reasonable and useful to classify Acetaminophen as an NSAID.

13 References

- ↑ Urban Dictionary: Vitamin I http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Vitamin%20I

- ↑ Skeletal Muscle PGF2αand PGE2 in Response to Eccentric Resistance Exercise: Influence of Ibuprofen and Acetaminophen http://jcem.endojournals.org/content/86/10/5067.long

- ↑ An In Vitro Investigation Into the Effects of Repetitive Motion and Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Medication on Human Tendon Fibroblasts http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/23/1/119

- ↑ Cost-conscious prescribing of nonsteroidal anti-in... [Arch Intern Med. 1992] - PubMed result http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1417372

- ↑ Sports Injuries - NSAIDs: Why We Do Not Recommend Them http://www.caringmedical.com/sports_injury/nsaids.asp

- ↑ Oral ibuprofen: evaluation of its effect on peritendinous adhesions and the breaking strength of a tenorrhaphy. [J Hand Surg Am. 1986] - PubMed result http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3511134#

- ↑ A cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor impairs ligament heal... [Am J Sports Med. 2001 Nov-Dec] - PubMed result http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11734496?dopt=Abstract&holding=npg

- ↑ NSAIDs Inhibit Tendon-to-Bone Healing in Rotator Cuff Repair http://www.shoulderdoc.co.uk/article.asp?article=295

- ↑ Effect of ibuprofen on the healing and remodeling of bone and articular cartilage in the rabbit temporomandibular joint http://www.joms.org/article/0278-2391%2892%2990276-6/abstract

- ↑ JBJS | Dose and Time-Dependent Effects of Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibition on Fracture-Healing http://www.jbjs.org/article.aspx?Volume=89&page=500

- ↑ Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs on Bone Formation and Soft-Tissue Healing -- Dahners and Mullis 12 (3): 139 -- Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons http://www.jaaos.org/cgi/content/abstract/12/3/139

- ↑ The effect of a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug... [Am J Sports Med. 1988 Nov-Dec] - PubMed result http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3239621?dopt=Abstract&holding=npg

- ↑ The influence of a cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitor on i... [Am J Sports Med. 2003 Jul-Aug] - PubMed result http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12860547

- ↑ Exertional rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure... [Sports Med. 2007] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17465608

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 http://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr/Abstract/2010/03000/Athletes,_NSAID,_Coxibs,_and_the_Gastrointestinal.11.aspx

- ↑ KIDNEY FAILURE AND ULTRAMARATHONING http://www.lehigh.edu/\~dmd1/kidney.html

- ↑ Recurrent rhabdomyolysis in a collegiat... [Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16540825

- ↑ NSAID Use Increases the Risk of Developing Hyponatremia duri... : Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise http://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Abstract/2006/04000/NSAID_Use_Increases_the_Risk_of_Developing.2.aspx

- ↑ http://journals.lww.com/cjsportsmed/Abstract/2007/01000/Exercise_Associated_Hyponatremia,_Renal_Function,.8.aspx

- ↑ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002934307001672

- ↑ http://journals.lww.com/cjsportsmed/Abstract/2003/01000/The_Incidence,_Risk_Factors,_and_Clinical.8.aspx

- ↑ Dumke, CL.; Nieman, DC.; Oley, K.; Lind, RH. (Aug 2007). "Ibuprofen does not affect serum electrolyte concentrations after an ultradistance run.". Br J Sports Med 41 (8): 492-6; discussion 496. Template:citation/identifier. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCheung-2003 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSmith-1992 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBaldwin_Lanier-2003 - ↑ Howatson, G.; van Someren, KA. (2008). "The prevention and treatment of exercise-induced muscle damage.". Sports Med 38 (6): 483-503. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ Mishra, DK.; Fridén, J.; Schmitz, MC.; Lieber, RL. (Oct 1995). "Anti-inflammatory medication after muscle injury. A treatment resulting in short-term improvement but subsequent loss of muscle function.". J Bone Joint Surg Am 77 (10): 1510-9. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Effect of Ibuprofen Use on Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness of the Elbow Flexors http://journals.humankinetics.com/jsr-back-issues/jsrvolume4issue4november/effectofibuprofenuseondelayedonsetmusclesorenessoftheelbowflexors

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Pizza, FX.; Cavender, D.; Stockard, A.; Baylies, H.; Beighle, A. (Feb 1999). "Anti-inflammatory doses of ibuprofen: effect on neutrophils and exercise-induced muscle injury.". Int J Sports Med 20 (2): 98-102. Template:citation/identifier. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Template:cite journal

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Template:cite journal

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Template:cite journal

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Donnelly, AE.; Maughan, RJ.; Whiting, PH. (Sep 1990). "Effects of ibuprofen on exercise-induced muscle soreness and indices of muscle damage.". Br J Sports Med 24 (3): 191-5. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Stone, MB.; Merrick, MA.; Ingersoll, CD.; Edwards, JE. (Nov 2002). "Preliminary comparison of bromelain and Ibuprofen for delayed onset muscle soreness management.". Clin J Sport Med 12 (6): 373-8. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Hasson, SM.; Daniels, JC.; Divine, JG.; Niebuhr, BR.; Richmond, S.; Stein, PG.; Williams, JH. (Jan 1993). "Effect of ibuprofen use on muscle soreness, damage, and performance: a preliminary investigation.". Med Sci Sports Exerc 25 (1): 9-17. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Template:cite journal

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Barlas, P.; Craig, JA.; Robinson, J.; Walsh, DM.; Baxter, GD.; Allen, JM. (Jul 2000). "Managing delayed-onset muscle soreness: lack of effect of selected oral systemic analgesics.". Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81 (7): 966-72. Template:citation/identifier. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Template:cite journal

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Riasati et al.: Aspirin and delayed onset muscle soreness ASPIRIN MAY BE AN EFFECTIVE TREATMENT FOR EXERCISE- INDUCED MUSCLE SORENESS | ResearchGate http://www.researchgate.net/publication/228091056_Riasati_et_al._Aspirin_and_delayed_onset_muscle_soreness_ASPIRIN_MAY_BE_AN_EFFECTIVE_TREATMENT_FOR_EXERCISE-_INDUCED_MUSCLE_SORENESS

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Francis, KT.; Hoobler, T. (Sep 1987). "Effects of aspirin on delayed muscle soreness.". J Sports Med Phys Fitness 27 (3): 333-7. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Dudley, GA.; Czerkawski, J.; Meinrod, A.; Gillis, G.; Baldwin, A.; Scarpone, M. (Jan 1997). "Efficacy of naproxen sodium for exercise-induced dysfunction muscle injury and soreness.". Clin J Sport Med 7 (1): 3-10. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Baldwin, AC.; Stevenson, SW.; Dudley, GA. (Aug 2001). "Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy after eccentric exercise in healthy older individuals.". J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56 (8): M510-3. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Lecomte, JM.; Lacroix, VJ.; Montgomery, DL. (Apr 1998). "A randomized controlled trial of the effect of naproxen on delayed onset muscle soreness and muscle strength.". Clin J Sport Med 8 (2): 82-7. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ "The Effect of Taking Naproxen Drug on the Level of Perceived Pain and Changes of CPK Serum after Eccentric Exercise - Harakat Volume: 37, Issue:". http://journals.ut.ac.ir/page/article-frame.html?langId=en&articleId=1003701. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Bourgeois, J.; MacDougall, D.; MacDonald, J.; Tarnopolsky, M. (Jan 1999). "Naproxen does not alter indices of muscle damage in resistance-exercise trained men.". Med Sci Sports Exerc 31 (1): 4-9. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ Template:cite journal

- ↑ Template:cite journal

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Sayers, SP.; Knight, CA.; Clarkson, PM.; Van Wegen, EH.; Kamen, G. (May 2001). "Effect of ketoprofen on muscle function and sEMG activity after eccentric exercise.". Med Sci Sports Exerc 33 (5): 702-10. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ van Wijck, K.; Lenaerts, K.; van Loon, LJ.; Peters, WH.; Buurman, WA.; Dejong, CH. (2011). "Exercise-induced splanchnic hypoperfusion results in gut dysfunction in healthy men.". PLoS One 6 (7): e22366. Template:citation/identifier. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ VAN Wijck, K.; Lenaerts, K.; VAN Bijnen, AA.; Boonen, B.; VAN Loon, LJ.; Dejong, CH.; Buurman, WA. (Dec 2012). "Aggravation of exercise-induced intestinal injury by Ibuprofen in athletes.". Med Sci Sports Exerc 44 (12): 2257-62. Template:citation/identifier. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ Vermeulen Windsant, IC.; Hellenthal, FA.; Derikx, JP.; Prins, MH.; Buurman, WA.; Jacobs, MJ.; Schurink, GW. (Apr 2012). "Circulating intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as an early marker of intestinal necrosis after aortic surgery: a prospective observational cohort study.". Ann Surg 255 (4): 796-803. Template:citation/identifier. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ Ibuprofen use during extreme exercise: ... [Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17596774

- ↑ Ibuprofen use, endotoxemia, inflammation, ... [Brain Behav Immun. 2006] - PubMed - NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16554145

- ↑ Ibuprofen Official FDA information, side effects and uses. http://www.drugs.com/pro/ibuprofen.html

- ↑ Ibuprofen/Famotidine Reduces Gastric Ulcer Incidence http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/732432

- ↑ Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: Results of a United States multicenter, prospective study - Larson - 2005 - Hepatology - Wiley Online Library http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.20948/pdf

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 Staggered overdose pattern and delay to hospital presentation are associated with adverse outcomes following paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04067.x/full

- ↑ FDA May Restrict Acetaminophen http://www.webmd.com/pain-management/news/20090701/fda-may-restrict-acetaminophen

- ↑ ACETAMINOPHEN (PARACETAMOL) http://www.chemicalland21.com/lifescience/phar/ACETAMINOPHEN.htm

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "DomsNsaids" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "um" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "HyldahlKeadle2010" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "Trappe-2011" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "Trappe-2002" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.

- Category:Pages with reference errors