Icing is a core part of my recovery process and I've consistently found it to dramatically improve muscle healing. Short periods of ice (~20 minutes) will reduce blood flow which may limit further damage due to excessive inflammation. Longer periods (several hours) of icing increases blood flow, which improves healing. It's vital to use ice (frozen water), not a gel pack to prevent skin damage and for effectiveness.

Contents

1 Cold Induced Vasodilatation

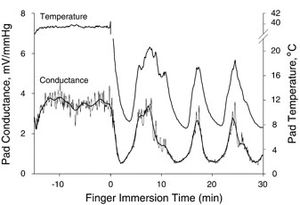

Cold initially reduces blood flow, but after about 20 minutes the body increases blood flow, possibly to prevent skin damage. This is called Cold Induced Vasodilatation (CIVD) and has been known about since 1930[1][2]). It's important to stay warm overall while icing a muscle, as reduced body temperature prevents CIVD[3][4]. This alternating reduction in inflammation and increased blood flow is believed to act as a 'pump', speeding up heeling. This cycle typically takes a few minutes, as shown below.

2 The (Lack) of Science

There is remarkably little science produced on Cold Induced Vasodilation. A 2004 analysis of the available research at the time stated "Currently, no authors have assessed the efficacy of ice in the treatment of muscle contusions or strains. Considering that most injuries are muscle strains and contusions, this is a large void in the literature." A 2008 study stated in its conclusion "There is insufficient evidence to suggest that cryotherapy improves clinical outcome in the management of soft tissue injuries"[5][6]. We'll therefore look at some anecdotal, real world experiences and recommendations.

3 Common Recommendations

The general recommendation for ice is to apply it for 20 minutes, then remove it for 20-60 minutes, repeating this cycle several times[7]. The general advice is to avoid applying ice for too long as it can damage the skin. I have found while this approach does help a little, it is not as effective as leaving the ice in place for a much longer period.

4 Longer Applications

Does a longer period make sense? Well, a Study has shown that the time needed to cool a muscle varies with the thickness of the fat surrounding the muscle. To lower the temperature 1 cm into the muscle by 7 degrees C, it takes ~8 minutes of ice for 0-10mm fat, but ~60 mins for 21-30mm fat[8]. This suggests that a simplistic 'apply for 20 minutes' guide is inappropriate; to impact tissue that is an inch deep would require at least an hour. One study[9] applied ice for 30 minutes and recorded the temperature at 1 and 2 cm into the muscle (below the fat layer). The results indicated that the minimum temperature was not reached during the application, but 6 to 9 minutes after the application finished. This suggests that 30 minutes was not sufficient to fully cool the muscle. Other factors to consider:

5 My Approach

My personal approach is to apply ice for much longer; often for hours continuously. I find that this produces much deeper healing and I have never had any problems. However, there are a number of conditions that would make this approach dangerous, such as poor circulation, diabetes or arthritis[12]. You should also be careful about applying ice for prolonged periods at joints such as elbow or ankle; the nerves are closer to the surface. I know some people like to use a compression bandage to hold the ice in place, adding compression to the cooling. Care should be taken after prolonged icing as the cooled muscles will have impaired control[13].

6 Frostbite and skin damage

Damage to cells occurs around -10c/14f[14][15], which is well below the temperature of ice. In fact, the temperature of the skin where it is in contact with an ice pack is normally about 5c/41f[16]. Animal studies that chilled the skin and underlying fat to between -1c/31f and -7c/19f showed no signs of tissue damage[17].

7 The Danger of Gel Packs, Ice Blocks, and Frozen Vegetables

I use ice cubes in a hefty Ziploc bag rather than gel packs as Gel packs start off too cold, and then warm up too quickly. If you use ice, the temperature will remain constant around freezing until all the ice is melted[12]. You should avoid large blocks of ice, as the ice will be at freezer temperature which is cold enough to damage the skin. The goal is to have a mixture of ice and water, which will be around freezing point. Likewise, frozen vegetables can remain too cold and do not result in a layer of water.

8 Monitoring Skin Temperature

You should monitor your skin temperature closely, and if it gets too cold you should stop. Generally, I find my skin temperature doesn't drop below 2c/35.6f and is typically warmer than that. I've used several different technologies for skin temperature monitoring, each with their own advantages.

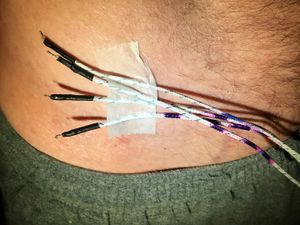

- A thermocouple is a temperature sensor on the end of a wire, which allows you to continuously monitor your skin temperature, and I have one that supports four sensors at the same time and is only Error: Could not parse data from Amazon!. This is probably the most cost effective approach.

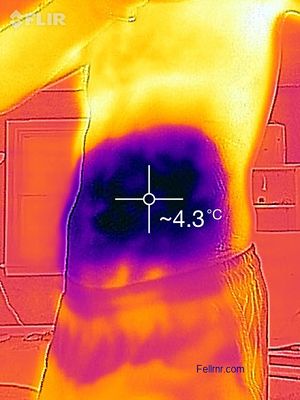

- A Thermal Camera is great as it allows you to see not only the temperature at one spot, but the pattern of temperature changes. The downsides are that you have to take the ice off to check the temperature, and the cameras are expensive. I'd use this with the above temperature sensor rather than instead of it. I recommend the FLIR ONE Error: Could not parse data from Amazon!, but check out Thermal Camera for more details.

An example image from my Thermal Camera showing the skin temperature.

An example image from my Thermal Camera showing the skin temperature.

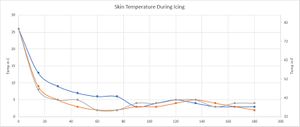

9 Typical Skin Temperatures

I've made a number of tests, monitoring my skin temperature for up to three hours. The graph below shows three tests where I took temperature readings every 15 minutes, and it's fairly typical of what I see. The skin temperature initially drops fairly quickly, dropping to around 5-15c/40-60f within five minutes, and stabilizing around 5-10c/40-50f within 15-20 minutes. After that, the temperature tends to be reasonably stable, and most of the variation is down to how much the ice water is moved. If the bag of ice water is kept very still, the skin temperature will rise somewhat, but if it's actively agitated, then the skin temperature can drop. It takes some effort for me to get the skin temperature below 2c/36f, and obviously, the skin temperature never drops below freezing, as the ice water isn't that cold.

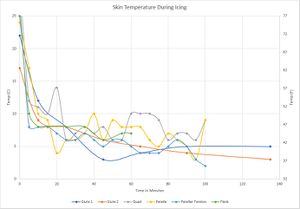

Here are some other tests I performed, showing some of the variation you might experience, with temperatures rising and falling.

10 Ice, Inflammation and Healing

A 2010 study[18] has shown that inflammation is necessary for healing, something that has been known for some time[19]. The study did not look at the use of ice for healing, only the role of inflammation itself, though it's conclusions were widely misinterpreted[20].

11 Ice and DOMS

Icing for short periods has been shown do make Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) worse[21]. In my experience, even longer periods of icing do not help much with DOMS.

12 See Also

13 References

- ↑ Lewis, Thomas. "Observations upon the reactions of the vessels of the human skin to cold." Heart 15.2 (1930): 177-208.

- ↑ C. O'Brien, Reproducibility of the cold-induced vasodilation response in the human finger., J Appl Physiol (1985), volume 98, issue 4, pages 1334-40, Apr 2005, doi 10.1152/japplphysiol.00859.2004, PMID 15579576

- ↑ HA. Daanen, Finger cold-induced vasodilation: a review., Eur J Appl Physiol, volume 89, issue 5, pages 411-26, Jun 2003, doi 10.1007/s00421-003-0818-2, PMID 12712346

- ↑ HA. Daanen, MB. Ducharme, Finger cold-induced vasodilation during mild hypothermia, hyperthermia and at thermoneutrality., Aviat Space Environ Med, volume 70, issue 12, pages 1206-10, Dec 1999, PMID 10596776

- ↑ TJ. Hubbard, CR. Denegar, Does Cryotherapy Improve Outcomes With Soft Tissue Injury?, J Athl Train, volume 39, issue 3, pages 278-279, 9 2004, PMID 15496998

- ↑ NC. Collins, Is ice right? Does cryotherapy improve outcome for acute soft tissue injury?, Emerg Med J, volume 25, issue 2, pages 65-8, Feb 2008, doi 10.1136/emj.2007.051664, PMID 18212134

- ↑ author Bryan A. Born, The Essential Massage Companion: Everything You Need to Know to Navigate Safely Through Today's Drugs and Diseases, date 1 January 2005, publisher Concepts Born, llc, isbn 978-0-9749258-0-6, pages 35–

- ↑ JW. Otte, MA. Merrick, CD. Ingersoll, ML. Cordova, Subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness alters cooling time during cryotherapy., Arch Phys Med Rehabil, volume 83, issue 11, pages 1501-5, Nov 2002, PMID 12422316

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 JE. Zemke, JC. Andersen, WK. Guion, J. McMillan, AB. Joyner, Intramuscular temperature responses in the human leg to two forms of cryotherapy: ice massage and ice bag., J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, volume 27, issue 4, pages 301-7, Apr 1998, doi 10.2519/jospt.1998.27.4.301, PMID 9549714

- ↑ Tsang, K. K. W., B. P. Buxton, and W. K. Guion. "The effects of cryotherapy applied through various barriers." Occupational Health and Industrial Medicine 2.38 (1998): 102.

- ↑ MA. Merrick, KL. Knight, CD. Ingersoll, JA. Potteiger, The effects of ice and compression wraps on intramuscular temperatures at various depths., J Athl Train, volume 28, issue 3, pages 236-45, 1993, PMID 16558238

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 MA. Merrick, LS. Jutte, ME. Smith, Cold Modalities With Different Thermodynamic Properties Produce Different Surface and Intramuscular Temperatures., J Athl Train, volume 38, issue 1, pages 28-33, Mar 2003, PMID 12937469

- ↑ R. Meeusen, P. Lievens, The use of cryotherapy in sports injuries., Sports Med, volume 3, issue 6, pages 398-414, 1986, PMID 3538270

- ↑ AA. Gage, What temperature is lethal for cells?, J Dermatol Surg Oncol, volume 5, issue 6, pages 459-60, 464, Jun 1979, PMID 110858

- ↑ AA. Gage, JA. Caruana, M. Montes, Critical temperature for skin necrosis in experimental cryosurgery., Cryobiology, volume 19, issue 3, pages 273-82, Jun 1982, PMID 7105779

- ↑ P. Janwantanakul, The effect of quantity of ice and size of contact area on ice pack/skin interface temperature., Physiotherapy, volume 95, issue 2, pages 120-5, Jun 2009, doi 10.1016/j.physio.2009.01.004, PMID 19627693

- ↑ MM. Avram, RS. Harry, Cryolipolysis for subcutaneous fat layer reduction., Lasers Surg Med, volume 41, issue 10, pages 703-8, Dec 2009, doi 10.1002/lsm.20864, PMID 20014262

- ↑ H. Lu, D. Huang, N. Saederup, IF. Charo, RM. Ransohoff, L. Zhou, Macrophages recruited via CCR2 produce insulin-like growth factor-1 to repair acute skeletal muscle injury., FASEB J, volume 25, issue 1, pages 358-69, Jan 2011, doi 10.1096/fj.10-171579, PMID 20889618

- ↑ DA. Alaseirlis, Y. Li, F. Cilli, FH. Fu, JH. Wang, Decreasing inflammatory response of injured patellar tendons results in increased collagen fibril diameters., Connect Tissue Res, volume 46, issue 1, pages 12-7, 2005, doi 10.1080/03008200590935501, PMID 16019409

- ↑ Putting ice on injuries could slow healing http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/8087777/Putting-ice-on-injuries-could-slow-healing.html

- ↑ Ching-Yu Tseng, Jo-Ping Lee, Yung-Shen Tsai, Shin-Da Lee, Chung-Lan Kao, Te-Chih Liu, Cheng-Shou Lai, M. Brennan Harris, Chia-Hua Kuo, Topical Cooling (Icing) Delays Recovery from Eccentric Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2012, pages 1, ISSN 1064-8011, doi 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318267a22c