The Science of the Long Run

While the Long Run is a core part of training for endurance races, there is relatively little scientific evidence available. A 2007 review study had a number of recommendations for long distance runners, but none around the Long Run[1]. This entry summarizes the evidence I have been able to locate.

Contents

1 Correlations between The Long Run and Performance

This section summarizes the studies that correlate the long run against various factors including marathon finish time and hitting the wall, or injury rate.

1.1 The Long Run and Marathon Performance

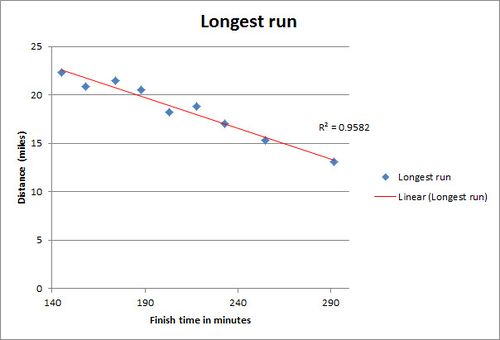

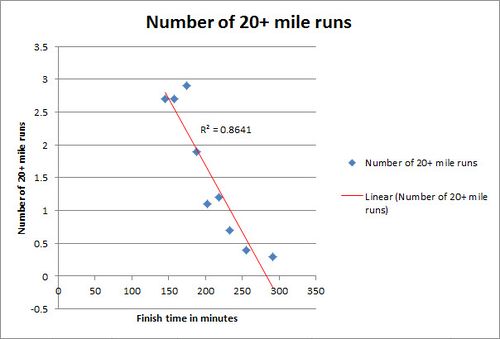

A 1970's study looked for correlations between marathon finish times and metrics from the final two months of training before the race[2]. There is an obvious correlation between the finishing time and both the longest run and overall mileage.

| Time | Max Week | Longest run | Number of 20+ mile runs | Mileage over two months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2:25:00 | 106 | 22.3 | 2.7 | 627 |

| 2:38:00 | 86 | 20.9 | 2.7 | 477 |

| 2:54:00 | 80 | 21.5 | 2.9 | 445 |

| 3:08:00 | 64 | 20.5 | 1.9 | 331 |

| 3:23:00 | 57 | 18.2 | 1.1 | 291 |

| 3:38:00 | 58 | 18.8 | 1.2 | 312 |

| 3:53:00 | 46 | 17 | 0.7 | 224 |

| 4:15:00 | 42 | 15.3 | 0.4 | 208 |

| 4:52:00 | 37 | 13.1 | 0.3 | 174 |

Another similar study showed that the number of runs over 16, over 20 miles, the length of the longest run and overall mileage are correlated with finish time[3]. One study separated out overall mileage from the long run[4]. In that study, two groups of runners did the same long run schedule but their overall weekly mileage either increased from 18 miles to 39 miles, or from 23 miles to 49 miles. The marathon performance was identical between the groups, suggesting that long run distance may be more important than overall mileage.

1.2 The Long Run and Hitting the Wall

A study of 315 marathon runners evaluated the factors that are correlated with reported 'Hitting the Wall'. The length of the longest run but not weekly mileage was correlated hitting the wall[5]. Further analysis showed that a longest long run of 20 miles or less increased the chance of hitting the wall by 50%[6]. Note that for these studies the definition of 'hitting the wall' was up to the subjects; they just had to consider themselves as having 'hit the wall'. While this lose definition has issues, the correlation is still useful as it indicates the runner encountered problems. Of particular interest is that the length of the longest run is the only training metric that correlated with 'hitting the wall'. This correlation may include physiological factors as well as physiological ones.

1.3 Injuries

I found no studies that showed a correlation between the length of the long run and injuries. There is some evidence that the increase in mileage[7], overall monthly mileage[8] or both[9] is correlated with injuries.

1.4 Correlation is not Causation

What little scientific evidence we have correlates better marathon outcomes with longer distance long runs. However, the evidence does not indicate if the longer distance long runs cause the improved marathon outcome or if better runners tend to do longer runs.

2 Glycogen Depletion

The evidence from the Glycogen depletion patterns may give some insight into the long run. We see that glycogen is depleted from some fibers before others[10]. This pattern suggests that some slow twitch fibers are used first, and as these become exhausted, other fibers are recruited in their place. Slow twitch fibers are used first, but over time more and more fast twitch fibers are recruited. This may be one mechanism behind the benefits of the long run; it exhausts the most accessible fibers and therefore trains the other fibers. It is possible that without the long run, only the same, easily recruited fibers are trained. It is also conceivable that by using fast twitch fibers for endurance exercise, the long run will change the nature of these fibers. The level of Glycogen depletion will depend on a number of factors, including:

- The initial level of Glycogen stores.

- A higher carbohydrate intake will tend to increase stored Glycogen.

- Prior exercise will decrease stored Glycogen.

- Carbohydrate taken during the run will tend to spare Glycogen.

- The longer the run, the more Glycogen will be used.

- The faster the pace, the more Glycogen will be used.

The last two factors, distance and pace are considered in my Long Run difficulty calculator that is part of my VDOT Calculator.

3 Muscle Damage

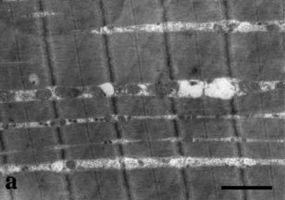

Running, and especially Downhill Running tends to produce muscle damage and Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. This damage immediately weakens the muscles, with recovery and remodeling of the muscle fibers taking around 14 days[11]. After a single bout of DOMS, the muscle fibers undergo 'profound adaptations' to be more resilient[11]. It seems reasonable that this mechanism is a key benefit of the Long Run. Therefore a long run should be long enough to create some muscle damage, while balancing the risk of injury. Similar muscle damage can be seen after a marathon that can take up to 8 weeks to recover from[12]. A study that looked at the effect of a 16 mile (26 Km) training run at around a 8:00 min/mile (5:00 min/km) pace on runners that had not run more than 9 miles (15 Km) before showed that while there were some markers of muscle damage in the blood, there was no muscle soreness as a result[13].

- Muscle damage from eccentric exercise (downhill running)

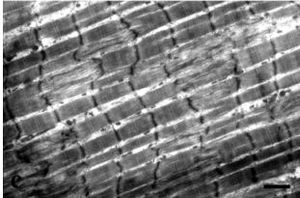

Muscle before downhill running[11]

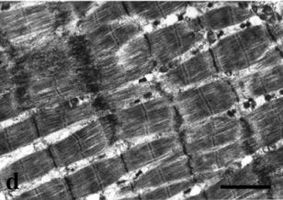

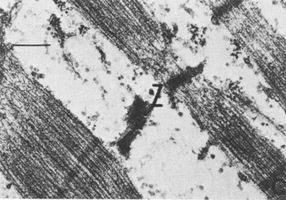

Immediately after downhill running[11]. Notice the disruption to the dark bands (z-bands) that are part of the muscle structure showing there is immediate damage.

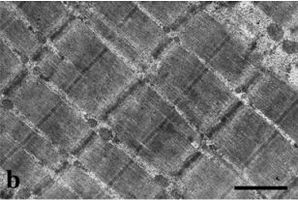

One day later[11], the damage and disruption is worse, indicated some continued breakdown.

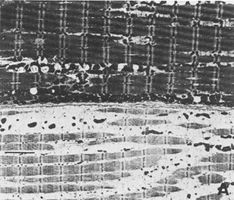

Muscle 14 days later[11], structurally recovered (other metrics do not return to pre-exercise levels at 14 days).

- Muscle damage after running a marathon

4 Anecdotal Advice

Given the limited scientific information, it seems reasonable to examine the anecdotal advice that is available.

- There are instances of remarkable performances without running long in training. For instance, Grete Waitz never ran more than 12 miles in training before winning the 1979 New York Marathon. However, at the time she was a world class track and cross country athlete who trained at 80-90 miles per week[14]. Her book on marathon training emphasizes the importance of the long run[15].

- Most training plans peak at 20 miles, though JD has 22 mile runs and Jeff Galloway has a 26 mile (2 min/mile slower with walking breaks)

- A consensus of caches suggests a single 20 mile run for novice marathoners and 3-6 long runs peaking at 23 miles for the more experience. [16].

- Some coaches recommend limiting the length of the long run to a percentage of the weekly mileage, often in the range 25-35%. The rationale for this unclear, and this recommendation could encourage high levels of Training Monotony.

- Using time rather than distance for long runs is sometimes suggested, as a 16 mile run at 11 min/mile would take a similar time to 22 miles at 8 min/mile. For instance, Jack Daniels does not recommend novice marathoners to do a long run longer than 2.5 hours[17]. This approach may be based around the belief that runs longer than 2 or 3 hours provide little or no additional benefit[18]. While there are some animal studies that show the benefits of endurance training plateaus, these studies looked at a limited aspect of endurance (cytochrome c)[19][20] and other animal studies do not show this plateau[21].

- It is often noted that ultramarathon runners do not train with proportionately long training runs. So a runner training for a 100 mile race will not run 76 mile long runs, which would be the equivalent to a 20 mile run for a marathon. In fact, the great ultrarunner Ray Krolewicz does not do training runs longer than 22 miles[22]. However, ultrarunners often run many long runs close together. For instance, Ray has done more than one 22 miler on each day of the weekend[22], and 'back to back' long runs of 20-30 miles are commonly prescribed[23]. Perhaps more importantly, ultrarunners typically do their long runs as a faster than race pace. Also, ultrarunners typically race frequently enough for the races to contribute to their overall training.

- It seems that many runners who run over 24 miles often do so in organized events, even if they are using the event for training rather racing.

5 Long run and total mileage

The effects of the length of the Long Run and the effects of total mileage are hard to distinguish. While there is the obvious interaction that the Long Run itself contributes to the overall mileage, there is the larger question of the relative importance of the two factors. It is generally accepted that a greater total mileage produces greater fitness adaptations up to a point, but diminishing returns occur at some level[24]. There is an intuitive interaction between total mileage and the Long Run, as a Long Run on fatigued legs from higher total mileage would have different consequences from a similar Long Run on fresh legs. Currently there does not appear to be sufficient evidence to understand how overall mileage and the length of the long run interact. Is it possible to mimic the benefits of a single long run with multiple shorter runs that have an incomplete recovery? This seems reasonable, though high mileage often produces high levels of Training Monotony and the risk of Overtraining.

6 Recommendations

It is hard to draw clear recommendations from the available scientific and anecdotal evidence. For some general guidelines see The Long Run.

7 References

- ↑ AW. Midgley, LR. McNaughton, AM. Jones, Training to enhance the physiological determinants of long-distance running performance: can valid recommendations be given to runners and coaches based on current scientific knowledge?, Sports Med, volume 37, issue 10, pages 857-80, 2007, PMID 17887811

- ↑ P. Slovic, Empirical study of training and performance in the marathon., Res Q, volume 48, issue 4, pages 769-77, Dec 1977, PMID 271323

- ↑ SJ. McKelvie, PM. Valliant, ME. Asu, Physical training and personality factors as predictors of marathon time and training injury., Percept Mot Skills, volume 60, issue 2, pages 551-66, Apr 1985, PMID 4000875

- ↑ FA. Dolgener, FW. Kolkhorst, DA. Whitsett, Long slow distance training in novice marathoners., Res Q Exerc Sport, volume 65, issue 4, pages 339-46, Dec 1994, PMID 7886283

- ↑ Matthew P. Buman, Britton W. Brewer, Allen E. Cornelius, Judy L. Van Raalte, Albert J. Petitpas, Hitting the wall in the marathon: Phenomenological characteristics and associations with expectancy, gender, and running history, Psychology of Sport and Exercise, volume 9, issue 2, 2008, pages 177–190, ISSN 14690292, doi 10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.03.003

- ↑ Matthew P. Buman, Britton W. Brewer, Allen E. Cornelius, A discrete-time hazard model of hitting the wall in recreational marathon runners, Psychology of Sport and Exercise, volume 10, issue 6, 2009, pages 662–666, ISSN 14690292, doi 10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.04.004

- ↑ SD. Walter, LE. Hart, JM. McIntosh, JR. Sutton, The Ontario cohort study of running-related injuries., Arch Intern Med, volume 149, issue 11, pages 2561-4, Nov 1989, PMID 2818114

- ↑ J. Lysholm, J. Wiklander, Injuries in runners., Am J Sports Med, volume 15, issue 2, pages 168-71, PMID 3578639

- ↑ M. Fredericson, AK. Misra, Epidemiology and aetiology of marathon running injuries., Sports Med, volume 37, issue 4-5, pages 437-9, 2007, PMID 17465629

- ↑ Selective glycogen depletion in skeletal muscle fibers of man following sustained contractions http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1331072/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Neuromuscular disease-associated proteins and eccentric exercise http://jp.physoc.org/content/543/1/297.full.pdf

- ↑ MJ. Warhol, AJ. Siegel, WJ. Evans, LM. Silverman, Skeletal muscle injury and repair in marathon runners after competition., Am J Pathol, volume 118, issue 2, pages 331-9, Feb 1985, PMID 3970143

- ↑ Timothy J. Quinn, Michelle J. Manley, The impact of a long training run on muscle damage and running economy in runners training for a marathon, Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness, volume 10, issue 2, 2012, pages 101–106, ISSN 1728869X, doi 10.1016/j.jesf.2012.10.008

- ↑ Grete Waitz's Tips For First-Time Marathoners http://running.competitor.com/2010/06/features/grete-waitz%E2%80%99s-tips-for-first-time-marathoners_10606

- ↑ Grete Waitz, Gloria Averbuch, Run your first marathon : everything you need to know to reach the finish lin, date 2010, publisher Skyhorse Pub., location New York, isbn 1-61608-036-1

- ↑ Hal. Higdon, Marathon : the ultimate training guid, date 2005, publisher Rodale, location Emmaus, Penn., isbn 1-59486-199-4

- ↑ Marathon Training: Shorten the Long Run | Active.com http://www.active.com/running/Articles/Marathon-Training--Shorten-the-Long-Run

- ↑ Are You Overemphasizing The Marathon Long Run? http://running.competitor.com/2012/07/training/are-you-overemphasizing-the-marathon-long-run_55719/2

- ↑ RL. Terjung, Muscle fiber involvement during training of different intensities and durations., Am J Physiol, volume 230, issue 4, pages 946-50, Apr 1976, PMID 178189

- ↑ GA. Dudley, WM. Abraham, RL. Terjung, Influence of exercise intensity and duration on biochemical adaptations in skeletal muscle., J Appl Physiol, volume 53, issue 4, pages 844-50, Oct 1982, PMID 6295989

- ↑ SK. Powers, D. Criswell, J. Lawler, LL. Ji, D. Martin, RA. Herb, G. Dudley, Influence of exercise and fiber type on antioxidant enzyme activity in rat skeletal muscle., Am J Physiol, volume 266, issue 2 Pt 2, pages R375-80, Feb 1994, PMID 8141392

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 TRAINING WISDOM FROM AN ULTRAMARATHONING LEGEND http://www.ncctrackclub.com/articles/RayKrolewiczLEGEND.html

- ↑ UltraLadies Running Club Trail 100-Mile Event Training Schedule - Trail Run Events http://www.trailrunevents.com/ul/schedule-100m.asp

- ↑ T. Busso, Variable dose-response relationship between exercise training and performance., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 35, issue 7, pages 1188-95, Jul 2003, doi 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074465.13621.37, PMID 12840641