Difference between revisions of "Cadence"

User:Fellrnr (User talk:Fellrnr | contribs) m |

User:Fellrnr (User talk:Fellrnr | contribs) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Rationale behind Cadence== | ==Rationale behind Cadence== | ||

Jack Daniels<ref name="jd"/> (the coach not the distiller) found that the slower the cadence, the longer you are in the air and the harder you land. Slow turn over means more impact, which causes more injury. | Jack Daniels<ref name="jd"/> (the coach not the distiller) found that the slower the cadence, the longer you are in the air and the harder you land. Slow turn over means more impact, which causes more injury. | ||

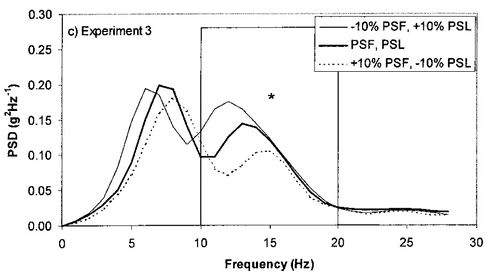

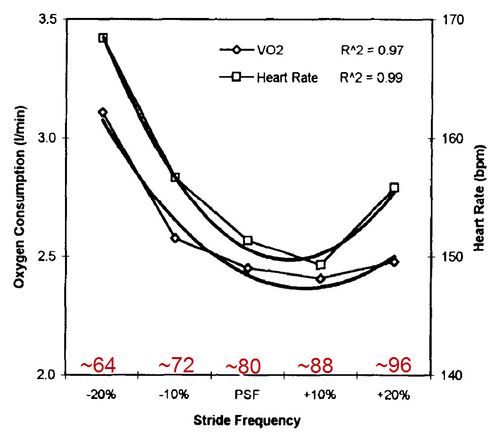

| − | If you take this to the extreme ('Reductio ad Absurdum'), imagine running with just one step per minute. You would have to leap high in the so that you would be in the air for 30 seconds; the landing force would probably break your legs. One study<ref name="WILLSON"/> showed that as people become tired, their cadence goes up, and with the higher cadence goes lower impact forces. | + | If you take this to the extreme ('Reductio ad Absurdum'), imagine running with just one step per minute. You would have to leap high in the so that you would be in the air for 30 seconds; the landing force would probably break your legs. Scientific studies have backed this up, showing that an increased cadence reduces the impact forces of running<ref name="Mercer-2003"/> with the peak impact force at a cadence of 88 being just over half that that of a cadence of 64<ref name="Hamill-1995"/>. A higher cadence also reduces peak leg deceleration as well as peak impact forces in the ankle and knee joints<ref name="Clarke-1985"/>. A cadence of around 90 is also associated with greater running efficiency than lower or higher cadences<ref name="Hamill-1995"/>. Not surprisingly, a higher cadence reduces [[Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness]] and the associated weakness<ref name="RowlandsEston2001"/>. One study<ref name="WILLSON"/> showed that as people become tired, their cadence goes up, and with the higher cadence goes lower impact forces. Although a shorter stride/faster cadence results in less landing force, a longer stride length/lower cadence is associated with less of the impact force reaching the head<ref name="Mercer-2003"/>. The impact forces at a longer stride length are mostly absorbed by the knee<ref name="Derrick-1998"/>. |

| − | + | [[File:Cadence and Impact.jpg|none|thumb|500px|This chart<ref name="Mercer-2003"/> shows the impact forces for three different cadences at the same speed. The thick line shows the Preferred Strike Frequency (PSF) and Preferred Strike Length (PSL), which was a cadence of 84. The thin line has the runners with a 10% slower cadence of 76 and 10% longer stride, shows increased impact. The dotted line shows 10% faster cadence of 93 and a reduced impact force.]] | |

| + | [[File:Cadence and VO2.jpg|none|thumb|500px|A chart showing the oxygen cost and heart rate for different cadences. (Cadence values in red added)<ref name="Hamill-1995"/>.]] | ||

==Correct Cadence== | ==Correct Cadence== | ||

So what should your cadence be? It seems that a turnover of 90 steps/minute is right for most people (180 steps/minute if counting both feet). To start off, check your cadence when you are running by counting how often your left foot touches the ground in a minute. If the number is 90 or higher, pat yourself on the back and go for another run. If the number is lower than 90, then you should look at changing your cadence. Your cadence does not have to be exactly 90, and is likely to change somewhat with your pace and terrain. A faster pace may have a higher cadence, as will up or down hill sections. My cadence now varies between 92 and 100 depending on pace. If your cadence was to vary between 88-92, you're doing well, though above 90 is preferable. A [[Best Running Watch|Good Running Watch]] will measure cadence using a [[Footpod]]. | So what should your cadence be? It seems that a turnover of 90 steps/minute is right for most people (180 steps/minute if counting both feet). To start off, check your cadence when you are running by counting how often your left foot touches the ground in a minute. If the number is 90 or higher, pat yourself on the back and go for another run. If the number is lower than 90, then you should look at changing your cadence. Your cadence does not have to be exactly 90, and is likely to change somewhat with your pace and terrain. A faster pace may have a higher cadence, as will up or down hill sections. My cadence now varies between 92 and 100 depending on pace. If your cadence was to vary between 88-92, you're doing well, though above 90 is preferable. A [[Best Running Watch|Good Running Watch]] will measure cadence using a [[Footpod]]. | ||

| − | |||

==Changing Cadence== | ==Changing Cadence== | ||

There are two ways of changing your cadence. The first is to try to change your cadence and then count for a minute to check the results. An easier way is to run with a metronome, which sets the pace for you. (A running watch that displays cadence is even better, but expensive.) | There are two ways of changing your cadence. The first is to try to change your cadence and then count for a minute to check the results. An easier way is to run with a metronome, which sets the pace for you. (A running watch that displays cadence is even better, but expensive.) | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

<ref name="jd">[[Jack Daniels Running Formula]] (second edition) Page 93-94, "Stride Rate"</ref> | <ref name="jd">[[Jack Daniels Running Formula]] (second edition) Page 93-94, "Stride Rate"</ref> | ||

<ref name="WILLSON">http://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Abstract/1999/12000/Plantar_loading_and_cadence_alterations_with.20.aspx Plantar loading and cadence alterations with fatigue</ref> | <ref name="WILLSON">http://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Abstract/1999/12000/Plantar_loading_and_cadence_alterations_with.20.aspx Plantar loading and cadence alterations with fatigue</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Derrick-1998"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Derrick | first1 = TR. | last2 = Hamill | first2 = J. | last3 = Caldwell | first3 = GE. | title = Energy absorption of impacts during running at various stride lengths. | journal = Med Sci Sports Exerc | volume = 30 | issue = 1 | pages = 128-35 | month = Jan | year = 1998 | doi = | PMID = 9475654 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Clarke-1985"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Clarke | first1 = TE. | last2 = Cooper | first2 = LB. | last3 = Hamill | first3 = CL. | last4 = Clark | first4 = DE. | title = The effect of varied stride rate upon shank deceleration in running. | journal = J Sports Sci | volume = 3 | issue = 1 | pages = 41-9 | month = | year = 1985 | doi = 10.1080/02640418508729731 | PMID = 4094019 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Hamill-1995"> Hamill, J., T. R. Derrick, and K. G. Holt. "Shock attenuation and stride frequency during running." Human Movement Science 14.1 (1995): 45-60.</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Mercer-2003"> {{Cite journal | last1 = Mercer | first1 = JA. | last2 = Devita | first2 = P. | last3 = Derrick | first3 = TR. | last4 = Bates | first4 = BT. | title = Individual effects of stride length and frequency on shock attenuation during running. | journal = Med Sci Sports Exerc | volume = 35 | issue = 2 | pages = 307-13 | month = Feb | year = 2003 | doi = 10.1249/01.MSS.0000048837.81430.E7 | PMID = 12569221 }}</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="RowlandsEston2001">{{cite journal|last1=Rowlands|first1=Ann V.|last2=Eston|first2=Roger G.|last3=Tilzey|first3=Caroline|title=Effect of stride length manipulation on symptoms of exercise-induced muscle damage and the repeated bout effect|journal=Journal of Sports Sciences|volume=19|issue=5|year=2001|pages=333–340|issn=0264-0414|doi=10.1080/02640410152006108}}</ref> | ||

</references> | </references> | ||

Revision as of 13:29, 1 February 2013

The single most important running tip I would give runners is to focus on their cadence (how often their feet touch the ground). Cadence is reasonably easy to modify and I believe it has more impact on running efficiency and injury than any other single thing.

Contents

1 Rationale behind Cadence

Jack Daniels[1] (the coach not the distiller) found that the slower the cadence, the longer you are in the air and the harder you land. Slow turn over means more impact, which causes more injury. If you take this to the extreme ('Reductio ad Absurdum'), imagine running with just one step per minute. You would have to leap high in the so that you would be in the air for 30 seconds; the landing force would probably break your legs. Scientific studies have backed this up, showing that an increased cadence reduces the impact forces of running[2] with the peak impact force at a cadence of 88 being just over half that that of a cadence of 64[3]. A higher cadence also reduces peak leg deceleration as well as peak impact forces in the ankle and knee joints[4]. A cadence of around 90 is also associated with greater running efficiency than lower or higher cadences[3]. Not surprisingly, a higher cadence reduces Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness and the associated weakness[5]. One study[6] showed that as people become tired, their cadence goes up, and with the higher cadence goes lower impact forces. Although a shorter stride/faster cadence results in less landing force, a longer stride length/lower cadence is associated with less of the impact force reaching the head[2]. The impact forces at a longer stride length are mostly absorbed by the knee[7].

2 Correct Cadence

So what should your cadence be? It seems that a turnover of 90 steps/minute is right for most people (180 steps/minute if counting both feet). To start off, check your cadence when you are running by counting how often your left foot touches the ground in a minute. If the number is 90 or higher, pat yourself on the back and go for another run. If the number is lower than 90, then you should look at changing your cadence. Your cadence does not have to be exactly 90, and is likely to change somewhat with your pace and terrain. A faster pace may have a higher cadence, as will up or down hill sections. My cadence now varies between 92 and 100 depending on pace. If your cadence was to vary between 88-92, you're doing well, though above 90 is preferable. A Good Running Watch will measure cadence using a Footpod.

3 Changing Cadence

There are two ways of changing your cadence. The first is to try to change your cadence and then count for a minute to check the results. An easier way is to run with a metronome, which sets the pace for you. (A running watch that displays cadence is even better, but expensive.)

An example of a small metronome would be Seiko DM50L Metronome - there are others like this. I trained for several months with a similar device, and it helped me immensely. I found it rather loud, so I wrapped it in duct tape to quieten it down.

4 The adaptation process

To start off, the change in cadence will feel very strange. I remember adjusting my cadence, and felt like my shoes were tied together! My steps were so short and fast that things felt all wrong. It took several weeks to adjust, but when the adjustment did take place, my running improved dramatically. I credit cadence as a key part of my success in going from a 4+ hour marathon to sub-3 hour and is one of my Running Breakthroughs.

5 See Also

- Arm Position

- Cadence Q and A

- http://www.active.com/running/Articles/Stride_right_and_improve_your_run.htm Stride right and improve your run

6 References

- ↑ Jack Daniels Running Formula (second edition) Page 93-94, "Stride Rate"

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Mercer, JA.; Devita, P.; Derrick, TR.; Bates, BT. (Feb 2003). "Individual effects of stride length and frequency on shock attenuation during running.". Med Sci Sports Exerc 35 (2): 307-13. Template:citation/identifier. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hamill, J., T. R. Derrick, and K. G. Holt. "Shock attenuation and stride frequency during running." Human Movement Science 14.1 (1995): 45-60.

- ↑ Clarke, TE.; Cooper, LB.; Hamill, CL.; Clark, DE. (1985). "The effect of varied stride rate upon shank deceleration in running.". J Sports Sci 3 (1): 41-9. Template:citation/identifier. Template:citation/identifier.

- ↑ Template:cite journal

- ↑ http://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Abstract/1999/12000/Plantar_loading_and_cadence_alterations_with.20.aspx Plantar loading and cadence alterations with fatigue

- ↑ Derrick, TR.; Hamill, J.; Caldwell, GE. (Jan 1998). "Energy absorption of impacts during running at various stride lengths.". Med Sci Sports Exerc 30 (1): 128-35. Template:citation/identifier.