Downhill Running and Training

By focusing on downhill running, I've been able to run 100 mile races without any Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. Focusing on the downhills is a critical training tool, and sadly one of the most ignored. While downhill running has obvious benefits for hilly races, it also protects your muscles from the damage of long distance races even on flat courses.

Contents

[hide]1 Why Downhill?

Many running plans include some "hill training", which generally consists of either running a hilly course, or running hard uphill to build strength, aerobic and anaerobic capacity. While these techniques can be useful, they do not provide the benefits of downhill training. While running uphill requires more energy, running downhill causes more muscle damage, which in turn creates resistance to that damage in the future.

2 The Damage and Benefits of Downhill Running

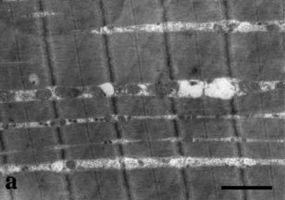

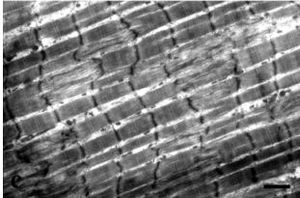

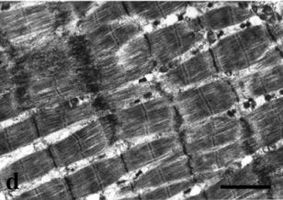

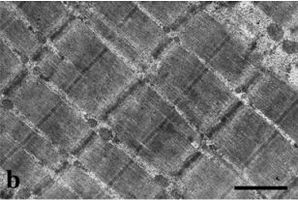

Downhill running is tough for several reasons, but the main one is that downhill running does more muscle damage. This damage causes immediate weakness in the muscles, as well as soreness in a day or two. If you've ever run a long steep descent and felt that your legs are numb or shaky, you've experienced this damage. The good news is that the more downhill running you do, the more you muscles adapt to be able to handle the strain. The images below are from sections through a muscle that has been damaged by downhill running. For details on the science behind downhill running, see Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness.

- Muscle damage from downhill running

Muscle before downhill running[1]

Immediately after downhill running[1]. Notice the disruption to the dark bands (z-bands) that are part of the muscle structure showing there is immediate damage.

One day later[1], the damage and disruption is worse, indicated some continued breakdown.

Muscle 14 days later[1], fully recovered

3 Downhill Training

There are various approaches to downhill training, each with their own benefits. By far the best approach is the Treadmill Descent, but you have to have a good treadmill you're prepared to abuse.

3.1 Run Hill Courses

The simplest approach to downhill training is to run a hilly course. Ideally, find a route that includes hills of varying steepness and length. It's important to focus more on the downhill sections that the uphill, which is a little counterintuitive. This approach can be thought of as a "Downhill Fartlek".

3.2 Downhill Intervals

Performing structured interval training around downhills is far better than simply running hilly courses, but not as effective as Treadmill Descents.

- Stage 1: Constant Pace Repeats. At this stage you will need a specific hill. Ideally it will be at least a quarter of a mile long and 6-8% gradient. Run up and down the hill with a fairly even pace. You are likely to be slightly slower uphill than downhill, but try to minimize the difference. Obviously the uphill will feel much harder than the downhill. Start with repeats totaling about 2 miles, and build up over time.

- Stage 2: Run Constant Effort Repeats. Running with the same effort up and down the hill will mean that you will be going much faster downhill than uphill. Compared with stage 1, your uphill running will be a little slower, and your Downhill Running quite a bit faster. Again, start with repeats totaling about 2 miles, and build up over time. You can use some stage 1 repeats to warm up.

- Stage 3: QU4DBUSTER. For the QU4DBUSTER, you are pushing your pace downhill hard, and recovering on the uphill run. Your downhill pace will be very fast, and you will need to have built up good leg strength and downhill form. Your pace should be a similar effort to your aerobic intervals (see Practical Aerobic Intervals and Aerobic Interval Training 101). You can use repeats from earlier stages to warm up.

- Stage 4: Anaerobic QU4DBUSTER. Running downhill fast enough to become anaerobic will build a lot of strength and speed, but these intervals should be used with caution. The speed you are running at will put a lot of stress on your body, and any biomechanical issues like Overstriding will cause injury. You must have a good foundation in the earlier stages and ease into these intervals slowly.

3.3 Treadmill Descents

When you run a hilly course or perform Downhill Intervals your legs will significantly recover on the uphill sections. If you have access to a really long hill then that will help, but for many of us, we don't have a multi-mile steep descent to use. Even if we did, the time taken to run up the hill reduces the time we can spend on the downhill. The answer is to run on a Treadmill that will provide a continual descent. I use the ProForm Pro 2000 with the back lifted on blocks for my Treadmill Descents, which is remarkably effective. Here are some tips on performing Treadmill Descents:

- Few treadmills will provide a descent without propping up the back. My ProForm Pro 2000 does offer limited descent options, but the maximum pace is too restricted to be useful.

- You will need to have a good Treadmill with a strong motor, as you'll be putting a lot of stress on it. The Pro 2000 has survived many long descent runs, but I weigh less than 140 pounds/70 Kg.

- I removed the cover from the motor of my Treadmill to improve cooling as the descents will stress the motor and control board. (You'll probably violate the warranty on your treadmill by propping up the back.)

- Start off with a gentle descent of -2 to -4 degrees and shorter distances. The Treadmill Descent may seem easy at the time, but the soreness will appear a day or too later.

- I've found that descent angle makes a bigger impact than you'd expect and the difficulty is non-linear. For instance, I've found that going from -12 to -14 degrees produces a radical increase in difficulty.

- A Treadmill Descent is quite easy aerobically, with a lower Heart Rate due to the decreased energy use. This can make it tricky to judge the difficulty, as the perceived effort can be quite low until the muscle damage is significant.

4 Downhill Technique

Cadence is always important in running, and especially in Downhill Running. Your Cadence should be faster downhill than on the flat, to help reduce the impact on your body. You must remain in control when running downhill; if you feel out of control or that you are flailing, you should slow up. You should try to combine the high Cadence with being relaxed and avoid tensing up. I find it important to keep my hips and back relaxed, otherwise a slight misstep will jar my back badly.

5 Race Strategy for Hilly Courses

Running efficiently downhill can make a significant difference to race performance. Running hard up the hills and recovering on the downhill makes for slower race times. An increase in intensity will make a small difference to the uphill pace, but it can make a large difference to the downhill pace. I've found that downhill training helps with flat races, especially longer ultramarathons. All running involves some of the stresses that cause Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness, and having resistance to this damage can keep you strong through to the end of the race. I consider downhill running one of my Running Breakthroughs.

6 The Difficulty of the Boston Marathon

The Boston Marathon is notorious for its difficulty and the famous "Heartbreak Hill." However, the reason Boston is a tough marathon is not the ascent up Heartbreak Hill, which is only about 90 feet/45 meters high, but the preceding descents that gradually destroy the quads.

7 The effect of steepness on DOMS

In my experience, the steeper descents produce a disproportionately severe level of DOMS. This is probably due to the muscles working at a longer length, as most[2][3] (but not all[4]) studies indicate longer muscle lengths produce greater DOMS. I've found when doing Treadmill Descents that a small increase in angle causes a lot more DOMS.

8 Running 100 Miles with No DOMS

Before starting the Treadmill Descents I would have massive DOMS after a 100 mile race, often hitting 4 or even 5 on the DOMS Scale. After many months of Treadmill Descents I've been able to run 100 Miles with little or no DOMS. I still have muscle damage and fatigue, but nothing like the problems I had before.

9 Feedback

A friend sent this feedback to my local running group…

I have enjoyed listening to Jonathan's thoughts and advice on many running topics, but one that I always struggled with was "running uphill is easy, it's the downhill that's hard." Now, on a theoretical level this made sense, because maintaining even effort on the uphill simply means shortening your stride, while running downhill can be a balance between going faster and maintaining control. My personal experiences with hill running have not been that they are easy. I'll be cruising along and see a hill approaching; my Heart Rate will surge in anticipation and I will grit my teeth in preparation for the charge up the hill. It doesn't help that there's also a little voice saying "you're going to have to run it twice." So here is my breakthrough for the day: I allowed myself to run easier on the uphills. Rather than tighten up in anticipation, I focused on staying relaxed, telling myself that it was OK to slow down, just keep my feet light and my turnover quick. Now, rather than exerting extra effort, I was Breathing easier and before I knew it I was over the top. I've always done pretty well going downhill, but I focused on an even effort and lengthened my stride only as much as necessary. An important note: it takes concentration on the downhills - you end up going pretty quickly, and you really don't want to get distracted. Maybe this will help someone else; I was just so pleased with my discovery I wanted to share. Today's hilly run turned out well: 2 mi hills, 6 mi pretty flat, 2 mi hills - overall average 7:14.

10 References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Neuromuscular disease-associated proteins and eccentric exercise http://jp.physoc.org/content/543/1/297.full.pdf

- Jump up ↑ DA. Jones, DJ. Newham, C. Torgan, Mechanical influences on long-lasting human muscle fatigue and delayed-onset pain., J Physiol, volume 412, pages 415-27, May 1989, PMID 2600839

- Jump up ↑ RB. Child, JM. Saxton, AE. Donnelly, Comparison of eccentric knee extensor muscle actions at two muscle lengths on indices of damage and angle-specific force production in humans., J Sports Sci, volume 16, issue 4, pages 301-8, May 1998, doi 10.1080/02640419808559358, PMID 9663954

- Jump up ↑ V. Paschalis, Y. Koutedakis, V. Baltzopoulos, V. Mougios, AZ. Jamurtas, G. Giakas, Short vs. long length of rectus femoris during eccentric exercise in relation to muscle damage in healthy males., Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), volume 20, issue 6, pages 617-22, Jul 2005, doi 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.02.011, PMID 15927735