Running Cadence

Cadence is a critical part of running, lowering the stress on ankles, knees, & feet, improving Running Economy, reducing injury rates, and enhancing Running Form. Cadence is how often your feet touch the ground and it's easy to modify.

Contents

1 Correct Cadence

So what should your cadence be? It's generally accepted that a turnover of 90 steps/minute is optimum for most people (180 steps/minute if counting both feet). To start off, check your cadence when you are running and if the number is 90 or higher, pat yourself on the back. If the number is lower than 90 then you should look at changing your cadence. Your cadence does not have to be exactly 90, and is likely to change somewhat with your pace and terrain. A faster pace may have a higher cadence, as will up or down hill sections.

2 Measuring Cadence

The cheapest way is to measure your cadence is to simply count how many times your foot touches the ground in a minute. However, it's much easier to use a running watch that displays cadence. Some watches will use a small Footpod attached to your shoe, but others make use of an internal accelerometer.

3 Changing Cadence

There are several ways of changing your cadence.

- To increase your cadence, focus on smaller steps rather than running faster. Initially this will feel strange, but it will become natural with time.

- The easiest way to get the right cadence is to run with a metronome, which sets the pace for you. An example of a small metronome would be the Seiko DM50 Metronome. I trained for several months with a similar device, and it helped me immensely. I found it rather loud, so I wrapped it in duct tape to quieten it down.

- You can also get a metronome app for a smartphone, but verify that the app is accurate as there are reports of some that do not keep time correctly.

- You can also remix music so that it is a higher tempo.

- Having the correct Arm Position is important for maintaining your cadence. If your arms are too low it will be quite difficult to keep your cadence high.

- Lighter shoes tend to raise running cadence, probably due to the extra effort required to move a heavy shoe backwards and forwards.

4 The adaptation process

To start off, the change in cadence will feel very strange. I remember adjusting my cadence, and felt like my shoes were tied together! My steps were so short and fast that things felt all wrong. It took several weeks to adjust, but when the adjustment did take place, my running improved dramatically. I credit cadence as a key part of my success in going from a 4+ hour marathon to sub-3 hour and is one of my Running Breakthroughs.

5 The Science of Running Cadence

Jack Daniels[1] (the coach not the distiller) found that the slower the cadence, the longer you are in the air and the harder you land. Slow turn over means more impact, which causes more injury. If you take this to the extreme ("Reductio ad Absurdum"), imagine running with just one step per minute. You would have to leap high in the so that you would be in the air for 30 seconds; the landing force would probably break your legs.

- Scientific studies have backed this up, showing that an increased cadence reduces the impact forces of running[2][3]

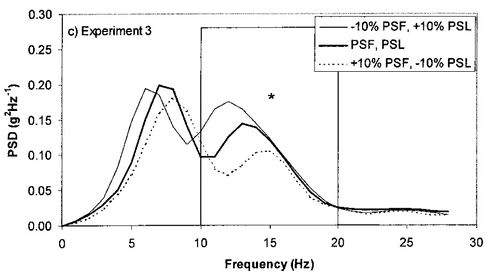

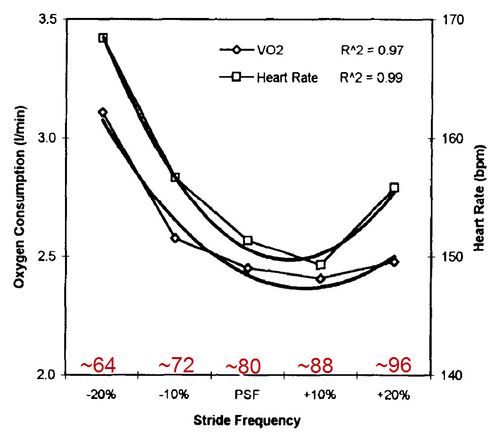

- The peak impact force at a cadence of 88 being just over half that that of a cadence of 64[4].

- A higher cadence also reduces peak leg deceleration as well as peak impact forces in the ankle and knee joints[5].

- Higher cadence is also related to a reduction in Overstriding[2].

- A cadence of around 90 is also associated with greater running efficiency than lower or higher cadences[4].

- Not surprisingly, a higher cadence reduces Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness and the associated weakness[6].

- One study[7] showed that as people become tired, their cadence goes up, and with the higher cadence goes lower impact forces. Although a shorter stride/faster cadence results in less landing force, a longer stride length/lower cadence is associated with less of the impact force reaching the head[3].

- The impact forces at a longer stride length are mostly absorbed by the knee[8].

- A review of the scientific studies showed consistently that an increased Cadence reduces shock at the hip, knee, and ankle, vertical oscillation, and ground contact time[9].

- Barefoot running tends to have a higher cadence than shod[10].

6 References

- ↑ Jack Daniels Running Formula (second edition) Page 93-94, "Stride Rate"

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 BC. Heiderscheit, ES. Chumanov, MP. Michalski, CM. Wille, MB. Ryan, Effects of step rate manipulation on joint mechanics during running., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 43, issue 2, pages 296-302, Feb 2011, doi 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ebedf4, PMID 20581720

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 JA. Mercer, P. Devita, TR. Derrick, BT. Bates, Individual effects of stride length and frequency on shock attenuation during running., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 35, issue 2, pages 307-13, Feb 2003, doi 10.1249/01.MSS.0000048837.81430.E7, PMID 12569221

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hamill, J., T. R. Derrick, and K. G. Holt. "Shock attenuation and stride frequency during running." Human Movement Science 14.1 (1995): 45-60.

- ↑ TE. Clarke, LB. Cooper, CL. Hamill, DE. Clark, The effect of varied stride rate upon shank deceleration in running., J Sports Sci, volume 3, issue 1, pages 41-9, 1985, doi 10.1080/02640418508729731, PMID 4094019

- ↑ Ann V. Rowlands, Roger G. Eston, Caroline Tilzey, Effect of stride length manipulation on symptoms of exercise-induced muscle damage and the repeated bout effect, Journal of Sports Sciences, volume 19, issue 5, 2001, pages 333–340, ISSN 0264-0414, doi 10.1080/02640410152006108

- ↑ http://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Abstract/1999/12000/Plantar_loading_and_cadence_alterations_with.20.aspx Plantar loading and cadence alterations with fatigue

- ↑ TR. Derrick, J. Hamill, GE. Caldwell, Energy absorption of impacts during running at various stride lengths., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 30, issue 1, pages 128-35, Jan 1998, PMID 9475654

- ↑ A. G. Schubert, J. Kempf, B. C. Heiderscheit, Influence of Stride Frequency and Length on Running Mechanics: A Systematic Review, Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, volume 6, issue 3, 2013, pages 210–217, ISSN 1941-7381, doi 10.1177/1941738113508544

- ↑ C. Divert, G. Mornieux, H. Baur, F. Mayer, A. Belli, Mechanical comparison of barefoot and shod running., Int J Sports Med, volume 26, issue 7, pages 593-8, Sep 2005, doi 10.1055/s-2004-821327, PMID 16195994