Difference between revisions of "Running Form"

User:Fellrnr (User talk:Fellrnr | contribs) |

User:Fellrnr (User talk:Fellrnr | contribs) |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

* '''Step Width'''. Changing your step width should be done carefully and gradually, as it will change the stress on your legs and hips. | * '''Step Width'''. Changing your step width should be done carefully and gradually, as it will change the stress on your legs and hips. | ||

* '''Imbalance'''. By far the best approach to detecting and resolving imbalances is to get an evaluation by a good sports doctor. They will check your range of motion and strength of various muscles and in many cases can resolve these problems. | * '''Imbalance'''. By far the best approach to detecting and resolving imbalances is to get an evaluation by a good sports doctor. They will check your range of motion and strength of various muscles and in many cases can resolve these problems. | ||

| + | =Running Form and the Treadmill= | ||

| + | It's commonly believed that the running form is different on a [[Treadmill]] when compared with running outside, and there is some scientific support for this belief. A comparison of runners on a [[Treadmill]] and outside found statistically significant differences in their running form, including knee movement, peak ground reaction force, joint moment, and joint power trajectories<ref name="Riley-2008"/>. However, the study concluded that the differences were small enough that evaluating running form on the [[Treadmill]] was still viable. Another study concluded that the differences between outside and [[Treadmill]] running were too large for [[Treadmill]]-based analysis to be acceptable<ref name="Youlian-2009"/>, while a third study concluded that [[Treadmill]] running was a reasonable representation of outside running for most, but not all subjects<ref name="Fellin-2010"/>. Interestingly, the studies generally showed a higher [[Cadence]] on the [[Treadmill]]. For most runners these differences are probably not a big deal. However, you should take care when transitioning from a period when most of your running is on the [[Treadmill]] to running outside or vice versa. This is especially true if you train for a race using only a [[Treadmill]]. It is best to try to transition from one to the other gradually, and possibly reduce your training volume during the transition. | ||

=Analyzing Running Form= | =Analyzing Running Form= | ||

With the exception of [[Cadence]], most aspects of your Running Form are not easy to check yourself, so here are a few techniques you can use. | With the exception of [[Cadence]], most aspects of your Running Form are not easy to check yourself, so here are a few techniques you can use. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 45: | ||

* '''The scrape'''. If you hear a scraping sound it means your feet are still moving horizontally when they touch down. If you hear this scraping sound, try to feel with your feet if your foot is pushing forward against the ground on contact or backwards. The most common situation is that your feet are pushing forward due to [[Overstriding]]. | * '''The scrape'''. If you hear a scraping sound it means your feet are still moving horizontally when they touch down. If you hear this scraping sound, try to feel with your feet if your foot is pushing forward against the ground on contact or backwards. The most common situation is that your feet are pushing forward due to [[Overstriding]]. | ||

* '''The slap'''. A hard slapping sound often indicates a high impact is occurring. This can occur for various reasons, and it's best to get someone to watch your running form or use [[High Speed Video Analysis]]. | * '''The slap'''. A hard slapping sound often indicates a high impact is occurring. This can occur for various reasons, and it's best to get someone to watch your running form or use [[High Speed Video Analysis]]. | ||

| − | * '''Symmetry'''. Your feet should sound the same, | + | * '''Symmetry'''. Your feet should sound the same, and any difference indicates an imbalance that should be corrected. This imbalance could be in flexibility, strength, leg length or some other factor. |

==Visual Inspection== | ==Visual Inspection== | ||

| − | The simplest way of having your running form analyzed is to get someone to watch you run. Having them watch you run on a | + | The simplest way of having your running form analyzed is to get someone to watch you run. Having them watch you run on a [[Treadmill]] is easiest, but be try to notice if your Running Form changes between outside running and the [[Treadmill]]. Some things the observer should look out for. |

* First, check the runner's [[Cadence]]. | * First, check the runner's [[Cadence]]. | ||

* Looking at the runner from the side: | * Looking at the runner from the side: | ||

| Line 78: | Line 80: | ||

<ref name="Ounpuu-1994"> S. Ounpuu, The biomechanics of walking and running., Clin Sports Med, volume 13, issue 4, pages 843-63, Oct 1994, PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7805110 7805110]</ref> | <ref name="Ounpuu-1994"> S. Ounpuu, The biomechanics of walking and running., Clin Sports Med, volume 13, issue 4, pages 843-63, Oct 1994, PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7805110 7805110]</ref> | ||

<ref name="Arellano-2011"> CJ. Arellano, R. Kram, The effects of step width and arm swing on energetic cost and lateral balance during running., J Biomech, volume 44, issue 7, pages 1291-5, Apr 2011, doi [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.01.002 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.01.002], PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21316058 21316058]</ref> | <ref name="Arellano-2011"> CJ. Arellano, R. Kram, The effects of step width and arm swing on energetic cost and lateral balance during running., J Biomech, volume 44, issue 7, pages 1291-5, Apr 2011, doi [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.01.002 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.01.002], PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21316058 21316058]</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Youlian-2009"> HONG, Youlian. "A Kinematic Comparison of Running on [[Treadmill]] and Overground Surfaces." XXVII International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports. Vol. 1. 2009.</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Riley-2008"> PO. Riley, J. Dicharry, J. Franz, U. Della Croce, RP. Wilder, DC. Kerrigan, A kinematics and kinetic comparison of overground and [[Treadmill]] running., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 40, issue 6, pages 1093-100, Jun 2008, doi [http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181677530 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181677530], PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18460996 18460996]</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Fellin-2010"> RE. Fellin, K. Manal, IS. Davis, Comparison of lower extremity kinematic curves during overground and [[Treadmill]] running., J Appl Biomech, volume 26, issue 4, pages 407-14, Nov 2010, PMID [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21245500 21245500]</ref> | ||

</references> | </references> | ||

Revision as of 07:43, 26 July 2013

The science behind running form is limited, but there are several aspects to running form that are generally recommended. This article covers some key components of running form, including a high Cadence, avoiding Overstriding and the need for a slight forward lean.

Contents

1 Running Form

1.1 Cadence

Main article: Cadence

Cadence, which is how often your feet touch the ground, is reasonably easy to modify and has a large impact on running form and running efficiency. You should aim for a cadence of around 180 steps/minute counting both feet, which is 90 steps/minute if you count just one foot. Initially this is likely to feel strange at first, like your Shoes are tied together, but after a few weeks it will become natural. A metronome can help you keep time, as can music remixed to 180 BPM or a sports watch with a Footpod.

1.2 Overstriding

Main article: Overstriding

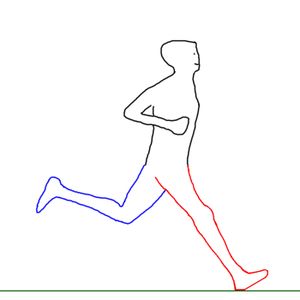

The picture below is an example of a common problem called overstriding. With overstriding, the foot lands ahead of the hips, which tends to cause braking forces and exacerbates heel strike.

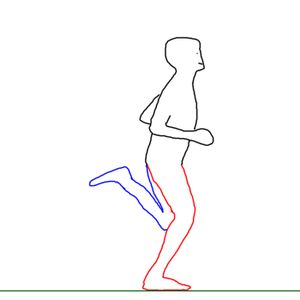

1.3 Forward Lean

The image below shows the slight forward lean of the body, putting the weight over the front of the foot. An easy way to get a sense of the right lean is to stand up naturally, then gently lean forward. You should feel your weight change from being over all of your feet equally to being over the front part of your foot, but don't lean so far forward that you are on your toes with your heels off the ground. This is the feeling you should have when running. Another way of getting a sense of the forward lean is to stand up tall, then lean forward until you have to start running to avoid falling over.

1.3.1 The Forward Lean and Gravity

The Pose method and Chi Running both talk about using gravity to pull you forward. While this is obviously nonsense from the perspective of the laws of physics, there is some basis for the idea. The forward lean does not cause gravity to "pull you along", but it does change the vector of the force your muscles are applying to your feet. If you are perfectly upright, your muscles are pushing down, with little or none of the force being directed backward to provide propulsion. As you lean forward, your muscles start to push both down and backwards, providing greater forward propulsion. It is possible to increase your speed by increasing your forward lean. Your muscles are still providing the propulsion, not gravity, but the extra forward lean does vector the muscular force better.

1.4 Run Tall

The back should be straight, without any hunching over or bending, but also without being rigid. A mental exercise to improve this is to imagine that there is a thread attached to the top of your head while you're running, and the thread is pulling you taller. If you look further ahead rather than down at your feet, this will help with your back angle as well as preventing excess strain on your neck.

1.5 Arm Position

Main article: Arm Position

A high cadence will naturally keep your arms high.Your arms should swing naturally, acting as a counterbalance to your running motion. You don't need to consciously drive your arms; just let them move naturally and freely. Your shoulders should be relaxed rather than hunched up. You may need to check for tension in your shoulders periodically and consciously relax them. Your hands should be relaxed and neither bunched into a fist or overly straightened.

1.6 Foot Strike

Main article: Foot Strike

Foot strike is which part of the foot lands first while running. Some runners land on their heels while others land on their forefoot. The optimal foot strike is controversial and there is insufficient evidence to make any clear recommendations. My recommendation is to focus on Cadence and reducing overstriding rather than changing your foot strike.

1.7 Step width

Most runners will naturally run with their feet landing close to the midline of their body. One study showed that runners generally prefer to have their feet land about 1.4 inches (3.6cm) from the midline, and changing to a wider landing pattern increased the energy cost of running by up to 11%[1]. This is probably not something that most runners need to worry about, but there are small percentages that have an unusually wide step width. This may be due to have a large muscle or fat mass on the inner thighs that interferes with leg movement, in which case compression clothing may help.

1.8 Imbalances

An imbalance or weakness can produce bad Running Form as well as causing injuries. One of the most dramatic examples is where one of the leg bones is a different length, which misaligns the feet, legs, hips and back. Other problems such as tight or weak muscles are more common, but also cause bad Running Form and injury.

2 Changing your running form

With the exception of Foot Strike and to a lesser extent step width, most aspects of Running Form are reasonably easy to change and have relatively low risk.

- Cadence. This is one of the easiest and best aspects of Running Form to change. It's trivial to check your current cadence and to monitor your progress. I believe improving your cadence provides the greatest improvement for the least effort and risk. It also seems that improving your cadence will often naturally improve other aspects of Running Form, including overstriding and foot strike.

- Overstriding. Reducing overstriding is reasonably easy and low risk. Significant overstriding can often be felt or seen by someone watching you run, and is not difficult to correct. Sometimes all that is needed is to avoid consciously reaching forward with your feet, and often overstriding is corrected with a higher cadence and a forward lean. Don't try to correct overstriding without correcting your cadence. High Speed Video Analysis is the best option for verifying your overstriding.

- Forward lean. The right forward lean is easy to learn, and goes hand in hand with avoiding overstriding.

- Run Tall. Avoiding a hunched back may take some effort, as runners who have this problem are often not aware of it, and tend to revert when they get tired. The mental exercise of imagining a thread pulling your head upwards can help.

- Arm Position. Improving your arm position is related to cadence, as a higher cadence needs a higher arm position. Having your hand too low will create a pendulum with a slow swing that makes having the right cadence tough. It should be simple to avoid consciously driving your arms harder, but keeping your shoulders, arms and hands relaxed requires a periodic check. We are rarely aware of how much tension is in our bodies, and it can help to occasionally drop your arms down and gently shake out your hands and arms.

- Foot Strike. This is by far the highest risk aspect of Running Form to change. Dramatic changes in foot strike from Rear Foot Strike to Forefoot Strike have been known to cause stress fractures and tendon problems in the foot. I would generally recommend gradual changes in foot strike, and improving cadence and reducing overstriding will often naturally move the initial strike location forward on the foot. If you do choose to make a dramatic change in your foot strike, I would suggest that you also dramatically reduce your mileage. It may be appropriate to go back to learning to run again, using a simple run walk pattern as noted in Starting to run. The more experienced you are and the higher your mileage, the greater the risk of a dramatic change in foot strike. This is because a change in foot strike is compounded by the miles you spend in the new style. Someone who runs 20 miles/day has 10 times the stress from a change compared with someone running 2 miles/day.

- Step Width. Changing your step width should be done carefully and gradually, as it will change the stress on your legs and hips.

- Imbalance. By far the best approach to detecting and resolving imbalances is to get an evaluation by a good sports doctor. They will check your range of motion and strength of various muscles and in many cases can resolve these problems.

3 Running Form and the Treadmill

It's commonly believed that the running form is different on a Treadmill when compared with running outside, and there is some scientific support for this belief. A comparison of runners on a Treadmill and outside found statistically significant differences in their running form, including knee movement, peak ground reaction force, joint moment, and joint power trajectories[2]. However, the study concluded that the differences were small enough that evaluating running form on the Treadmill was still viable. Another study concluded that the differences between outside and Treadmill running were too large for Treadmill-based analysis to be acceptable[3], while a third study concluded that Treadmill running was a reasonable representation of outside running for most, but not all subjects[4]. Interestingly, the studies generally showed a higher Cadence on the Treadmill. For most runners these differences are probably not a big deal. However, you should take care when transitioning from a period when most of your running is on the Treadmill to running outside or vice versa. This is especially true if you train for a race using only a Treadmill. It is best to try to transition from one to the other gradually, and possibly reduce your training volume during the transition.

4 Analyzing Running Form

With the exception of Cadence, most aspects of your Running Form are not easy to check yourself, so here are a few techniques you can use.

4.1 Listen to Your Feet

The sound your feet make when they land can tell you a lot about your Running Form.

- The pat. A good running form will have a sound like your feet are gently patting the ground. Generally speaking, the quieter your feet land the better.

- The scrape. If you hear a scraping sound it means your feet are still moving horizontally when they touch down. If you hear this scraping sound, try to feel with your feet if your foot is pushing forward against the ground on contact or backwards. The most common situation is that your feet are pushing forward due to Overstriding.

- The slap. A hard slapping sound often indicates a high impact is occurring. This can occur for various reasons, and it's best to get someone to watch your running form or use High Speed Video Analysis.

- Symmetry. Your feet should sound the same, and any difference indicates an imbalance that should be corrected. This imbalance could be in flexibility, strength, leg length or some other factor.

4.2 Visual Inspection

The simplest way of having your running form analyzed is to get someone to watch you run. Having them watch you run on a Treadmill is easiest, but be try to notice if your Running Form changes between outside running and the Treadmill. Some things the observer should look out for.

- First, check the runner's Cadence.

- Looking at the runner from the side:

- Check for Overstriding by looking for where the foot makes contact in relation to the hip; is it directly below, or ahead.

- What is the angle of the foot on first contact? This is a good indication of Foot Strike, and a hard heel strike, where the forefoot is elevated and they land on the extreme back of the heel is a bad sign.

- How much are the hips rotating? Are the hips rotating equally for the left and right swings?

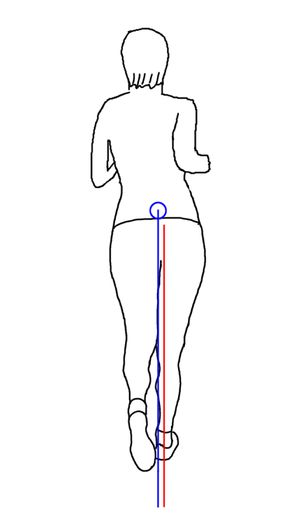

- Looking from the rear:

- Is there a large Step Width, with the feet landing far apart, or do they cross the midline slightly?

- How much are the hips swinging and are they swinging symmetrically? (Too much swing may indicate weak glutes.)

- From the rear, do the legs look straight or are the knees buckling inwards?

4.3 High Speed Video Analysis

Visual inspection of a runner is good, but the movements of running occur quickly and it's tricky for even the most experienced person to catch the details. High Speed Video Analysis is a far better option and can be done reasonably cheaply.

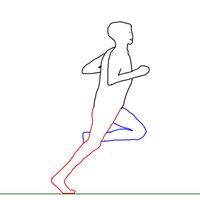

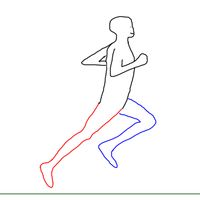

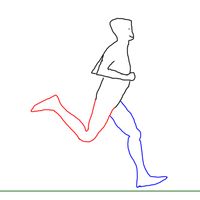

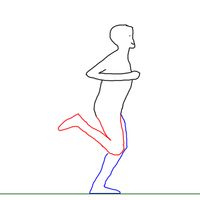

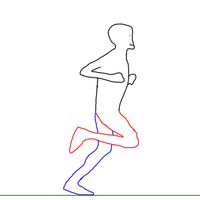

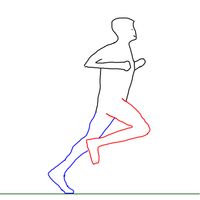

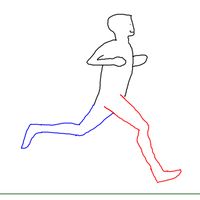

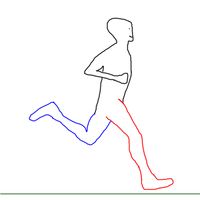

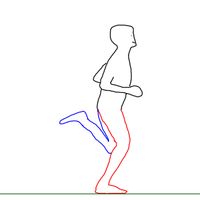

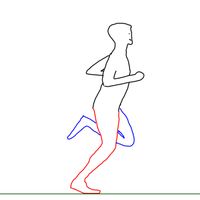

5 Running Movements

The images below show the sequence of movements that make up running, along with notes describing the action and muscles involved[5]. The descriptions focus on the right leg, shown in red and show a complete cycle.

- Running Form

6 References

- ↑ CJ. Arellano, R. Kram, The effects of step width and arm swing on energetic cost and lateral balance during running., J Biomech, volume 44, issue 7, pages 1291-5, Apr 2011, doi 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.01.002, PMID 21316058

- ↑ PO. Riley, J. Dicharry, J. Franz, U. Della Croce, RP. Wilder, DC. Kerrigan, A kinematics and kinetic comparison of overground and Treadmill running., Med Sci Sports Exerc, volume 40, issue 6, pages 1093-100, Jun 2008, doi 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181677530, PMID 18460996

- ↑ HONG, Youlian. "A Kinematic Comparison of Running on Treadmill and Overground Surfaces." XXVII International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports. Vol. 1. 2009.

- ↑ RE. Fellin, K. Manal, IS. Davis, Comparison of lower extremity kinematic curves during overground and Treadmill running., J Appl Biomech, volume 26, issue 4, pages 407-14, Nov 2010, PMID 21245500

- ↑ S. Ounpuu, The biomechanics of walking and running., Clin Sports Med, volume 13, issue 4, pages 843-63, Oct 1994, PMID 7805110