What to Look for in Running Shoes

My running shoe reviews are based around my personal experience and my interpretation of The Science of Running Shoes. I believe that a good running shoe should not interfere with your natural biomechanics, so shoes with raised heels (drop) or anti-pronation features are a bad idea. A running shoe is a trade-off between weight, cushioning, and longevity, and different runners will want to make different trade-offs, so I cover shoes that vary in their characteristics, with the best shoes offering the most cushioning for their weight, from the light & minimalist shoes up to the heavier Maximalist shoes. I also believe that a good running shoe should match the shape of the human foot, without binding the toes.

- Fit. The fit of a shoe is quite personal, so while I talk about problems with the forefoot not matching the shape of the human foot, I don't go into details on the overall fit. My advice is to buy shoes from somewhere that provides free shipping both ways and to try them on at home. That way you can see how they fit for a longer period of time. I will often order shoes in two different sizes and return the one that does not fit as well. Alternatively, find a good running store that allows you to spend some time trying them out.

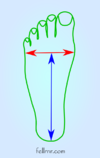

- Length & Width: When evaluating the fit of a shoe, the primary concern is the width across the metatarsal heads (forefoot) and the length from the rear to the metatarsal heads. Don't confuse the shape of the toe box with the width of the shoe, as the two are largely independent. Some shoes are available in wider/shorter sizes and sometimes even narrower/longer sizes, which may help if your forefoot-to-length ratio is different to the average.

- Toe Box. It seems bizarre, but the shape of a typical running shoe does not match the shape of the human foot. This creates the most problems in the front of the shoe, where the toe box tends to squash the toes, and prevent the natural movement. Thankfully, shoe design is slowly adapting, and there are now a number of manufacturers producing shoe designs that are suitable for use with the human foot.

- Volume. The volume of your foot can be important for hit. Typically, this is mostly an issue over the metatarsal heads, in front of the tongue. The tongue allows for quite a bit of variation in volume over the bulk of the foot, but ahead of the tongue a larger volume foot can get compressed.

- Heel Width. The shoe should adapt to varying width heels, but extremely narrow heels may have issues with the heel sliding around or coming away from the shoe.

- Undone Testing. One test I've found useful is to walk around in shoes with the laces fully undone. If the shoe fits properly the heel will stay in place and the shoe will move with my foot even though the laces are undone. After this quick test, I then move onto lacing up and testing while running.

- Length & Width: When evaluating the fit of a shoe, the primary concern is the width across the metatarsal heads (forefoot) and the length from the rear to the metatarsal heads. Don't confuse the shape of the toe box with the width of the shoe, as the two are largely independent. Some shoes are available in wider/shorter sizes and sometimes even narrower/longer sizes, which may help if your forefoot-to-length ratio is different to the average.

- Familiarity. There is reasonable evidence that runners will adapt based on their training, something that makes intuitive good sense. Part of that adaptation is to the shoes that are normally worn, so any radical change in shoe design can be disruptive, and possibly lead to injury. This is particularly true when moving to a more minimalist running shoe. Therefore, if you're looking for running shoe that is radically different to what you use too, it would be prudent to migrate through intermediary types of shoe. For instance, if you reduced to running in a traditional running shoe but want to move to a zero-drop shoe, you could use something like the Saucony Kinvara as a half-way house.

- Weight. Probably the most critical feature of the shoe is its weight, as relatively small increases in the weight of the shoe create a surprisingly large increase in the effort it takes to run. A general estimate is that each 3.5oz/100g increases the effort by 1%.

- Cushioning. While cushioning does not appear to be effective at reducing impact, The Science of Running Economy indicates that cushioning can reduce the effort it takes to run. In addition, I found that the highly cushioned shoes I refer to as Maximalist can reduce how sore my feet become on ultramarathons. However, cushioning adds weight, so the right shoe for you will be the right balance of cushioning and weight, and the best shoes provide the highest level of cushioning for their weight. Cushioning comes from the combination of the thickness and firmness of the midsole, though the shape of the midsole can also make a difference, as a flat-bottomed midsole has less cushioning than an "egg crate" shaped midsole. The insole can also make a difference to the cushioning, but beware that insoles tend to wear out much faster than the midsole foam. Cushioning is quite subjective, as there are also factors around how quickly a type of foam deforms, which can change how a shoe feels. That makes it hard to put a single value on cushioning, but I've combined all these factors into a number for comparison purposes.

- Performance Penalty. Most studies show that for each 3.5oz/100g of shoe weight performance drops by 1%. However, there is also good evidence that cushioning can improve performance, so some allowance is made for the padding. I give figures for the slowdown based on 4-hour marathon pace, which is 9:09 min/mile or 5:41 min/Km pace.

- Longevity. How long a shoe lasts normally depends on the foam midsole. In shoes where the foam midsole is not covered by a hard rubber outsole, the life of the shoe is may be limited by how quickly the midsole wears away due to abrasion from the ground. Different types of foam have at differing levels of abrasion resistance, and some softer foams run on hot, abrasive surface can wear away frighteningly quickly. However, it's more common for the life of the shoe to be limited by how quickly the foam breaks down, losing its shape and cushioning. I've found that the insole breaks down faster than the midsole, but both wear our far quicker than the outsole. This compression of the foam is typically uneven, which creates additional twisting forces on your foot. For minimalist shoes like the Merrell trail glove that have little or no midsole, the life of the shoe is limited by how long the outsole lasts, and these shoes typically lost vastly longer than the cushioned counterparts.

- Interference. Many shoes are designed to have features that are intended to interfere with the natural running stride. Shoes manufacturers try to use cushioning to reduce impact, medial posts to reduce Pronation, and a raised heel (drop) to reduce Achilles' tendon stress. However, there is evidence from The Science of Running Shoes that this interference is both unwarranted, and ineffectual.

- Drop. Since the 1980s shoes have had a higher heel than the forefoot in an attempt to reduce the strain on the calf and Achilles' tendon, something that has shown to be ineffective. The extra height in the heel can encourage an excessive heel strike and produces a shoe with relatively little forefoot cushioning. The extra height in the heel is called "drop", and shoes that have the same thickness at the heel and forefoot are referred to as "zero drop". While I believe a zero-drop shoe is best, a drop of 4-5 mm is not overly intrusive. The amount of drop depends on how softly and thickly cushioned the shoe is. A thick, soft shoe will compress more and reduce the perceived drop. For example, the Hoka Clifton is softly cushioned and is 32mm/28mm, giving a 4mm drop. If the shoe compresses by 20% on landing, this will give 22.4mm/25.6mm for a ~3mm drop. I've included values for "loaded drop" that reflect the drop when the shoe is worn. Note that I measure drop from under the ball of the foot and under the heel, and different locations in the shoe can produce different values.

- Structure. The issues cushioning comes predominantly from the foam midsole, which can be a single density, or have multiple densities in an attempt to reduce pronation. The denser foam is also heavier, and the more extreme anti-pronation measures found in motion control shoes are correlated with higher levels of pain and injury. Therefore, I believe that a shoe should have a single density of foam; simple is better.

- Flexibility. I believe that a shoe should be as flexible as possible, to allow a natural running style. However, high levels of cushioning create some intrinsic inflexibility, so this is another balancing act. Many shoes include grooves cut into the foam midsole in order to improve flexibility. (There is some evidence that a shoe that is "springy" may improve running economy.)

- Outsole. The foam used in the midsole is not terribly hard wearing, so it is frequently covered by a layer of hard rubber. Unfortunately, this hard rubber is also quite heavy, creating another balance, this time between weight and longevity. Recent developments in foam technology of the created midsoles that are hard wearing enough to be exposed, though they are never as hard wearing as a true outsole.

- Stone Traps. What out for holes in the sole of the shoe that can act as stone traps. Getting a small stone wedged into your shoe when you run across gravel can be painful, and sometimes they can be a real pain to extract.

- Upper. The upper of a running shoe is there to keep the sole attached to your foot. There are several things to look for in the upper:

- Flexibility. A flexible upper can be more comfortable as it accommodates slightly different shaped foot's. However, this flexibility involves elasticity that creates a continual pressure that can cause problems. Most shoes tend to have inflexible uppers, though this seems to be changing over time, with newer shoes having stretchy, sock like uppers.

- Seams. While it is possible to make a seamless, many shoes have uppers made of multiple materials to provide different levels of flexibility and reinforcement. Where these materials join they can be a seam that can rub and cause blisters. Modern manufacturing techniques have made seamless shoes more common, but there can be overlays that reinforce the shoe that can still cause issues.

- Breathability. Because your feet have a higher density of sweat glands than anywhere else in your body (except your hands), it's important for a shoe to breathe well.

- Padding. Padding can improve comfort and reduce blisters, especially where the shoe has seams. Padding is especially important around the ankle opening.

- Waterproofing. It seems like a waterproof shoe would keep your feet dry, but in practice it rarely works. While the waterproof layer might help if you step in a puddle, mostly the waterproof membrane holds more water in than it keeps out. This water either hits your legs and runs down into your shoes or sweat builds up faster than it can get through the permeable membrane. If you're hiking, you might be moving slow enough for sweat not to be an issue and if you're wearing waterproof jacket and trousers then waterproof boots can keep your feet dry. I've found that non-waterproof shoes with waterproof socks can be a better compromise for hiking in wet weather, but for running, it's best to accept the wet feet.

- Drainage. Conversely, a shoe that drains well can help prevent you shoes filling with water. That situation means your shoes are heavier and your feet immersed in water, which is unpleasant at best. Most shoes drain pretty well, and I've rarely found drainage holes to help. More often these drainage holes end up as stone traps, and require me to stop to clean them out.

- Tongue. The main problem with the tongue of a running shoe is that it can slip to the side. Manufacturers have various ways for addressing this problem, such as attaching parts of the tongue to the upper on one or both sides. A more extreme approach is to have a tongueless upper, sometimes called a "sock upper." The downside to a sock upper is that it requires a lot of flexibility in the material so you can get the shoe on your foot, and these approaches rarely work as well has a traditional tongue.

- Lacing. Given that shoelaces have been around since 3500 BC, it seems amazing that shoe manufacturers can find ways of screwing up this simple concept. The main thing you want from shoelaces is for them to stay tied while you're running. A shoelace that comes undone during a race can be disastrous. Generally, I find that flat laces work well, and round laces work poorly.

- Heel Counter. To try to bind the rear of the shoe to the heel of the foot, the part of the upper that goes around the back of the shoe is often made of a much stiffer material. As far as I can tell, this is another counterproductive feature that adds no value, but has the potential to cause problems.

1 Trail Running

What to look for in a trail running shoe will depend a lot on the type of trail surface you're running on. If you're running on a reasonably level, well-groomed gravel path, then this is probably close enough to running on asphalt or concrete that you don't need to worry about different shoes. Other types of trail require different things from your running shoes, so instead of looking at different aspects of the shoes, I'll look at different surfaces and what they require.

- Muddy. The muddier the trail, the more aggressive lugs you want on the sole of your shoes. This is exemplified by the Inov-8 Mudclaw or X-Talon, which have widely spaced 8 mm lugs designed specifically for soft mud. The problem I have found with this style of shoe is that it doesn't tend to work as well on harder surfaces, and I think the issue with more adaptability is better unless you know that specific runs are going to be overwhelmingly muddy. My other concern is that while the aggressive lugs will work better on somewhat muddier surfaces, you rapidly reach a point where things are so soft and slick that nothing much helps. My suggested compromise is to have at least 4 mm lugs unless you are looking for a dedicated pair of mud running shoes.

- Rocky Caltrops. Since ancient times, caltrops have been weapons to slow up or disable those on foot, and some trails can feel like they are an endless series of natural rocky caltrops. These trails have endless sharp points that injure the soles and can make running a misery. The pain can be reduced by landing softly and allowing your foot to mold to the shape of the land, but this tends to be a lot slower and there are limits to how effective it can be. On these trails a protective shoe can be a real boon. This protection comes from the combination of the thickness and softness of the midsole. At one extreme there is the thin sole that has a hard plate that spreads the forces of a rocky point, and the other extreme is a thick, softly cushioned shoe that molds around the rocky point. For instance, the Altra Timp has similar protection to the Altra Olympus, with the Timp having 28mm of firmer foam and the Olympus 34mm of softer foam. Getting the right level of protection will depend on many factors, including how vicious the trail is, how heavy you are, your running style, how steep the trail is, and other factors, plus personal preference. An insufficiently protected shoe will force you to slow down, picking your way through the pointy rocks, so you need something with the right blend of thickness and cushioning.

- Monkey Heads. One of the challenges all of trail running is those moderate sized rocks that tend to cause twisted ankles. I've often heard them referred to as "monkey heads", and a trail full of them makes it almost impossible to find a landing spot that's not going to put a lot of twisting stress on your ankle. The thicker the sole on your running shoe, the more these twisting stresses are amplified, making an ankle sprain more likely.

- Dusty. Really fine dust will penetrate most shoes and can be quite abrasive. A gaiter can help keep the dust out of the top of the shoe, as well as preventing your laces snagging. Altra shoes have attachment points for gaiters which is nice, or Dirty Girl Gaiters come with Velcro you can stick on.

- Slick Rock. Wet rock, especially at stream crossings can be dangerously slick. The best (or least bad) material I've found is an outsole that uses RMAT, but even Hoka has moved away from that as an outsole. In some situations, an aggressive lug pattern can bite through the slipperiness, but most of the time you just have to be careful.

- Grass & Gravel. For road shoes, I often have to cut open the toe box as few shoes are designed to fit a healthy human foot. However, for trail shoes this can cause problems, as you need the intact toe box to keep debris out. I've only found this to be a problem when running through grass or into mud, or walking over gravel, but others have found this to be more of an issue. While I'd like all running shoes to be shaped to fit a healthy human foot, this is more of an issue for trail shoes.

2 Foot Shape

Very few shoes have a shape that mirrors the human foot. It often seems like shoe companies have never seen a human foot before given the strange shape they make their shoes. This is especially true of Hoka, which have a particularly small toe box. The main company with shoes for the human foot is Altra, and once you've tried their shoes the traditional shoe shape seems even more bizarre. (The Mizuno Cursoris is a notable exception that also has a nice toe box shape.)

3 The Outsole Rubber

To achieve a light weight with maximum cushioning, many shoes don't use a hard rubber outsole over the softer midsole. This can result in uneven wear patterns when the midsole erodes away from around the patches of outsole. In the image below, the red arrows mark the soft midsole and the blue arrows mark the hard outsole, with the green arrow indicating an intermediate toughness material.